Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to keep up with education news from Denver and around the state.

In a closed-door meeting the day after a shooting at East High School in March, Denver school board members worried about being blamed, about Superintendent Alex Marrero overriding their authority by returning police to schools, and about the technicalities of how to proceed.

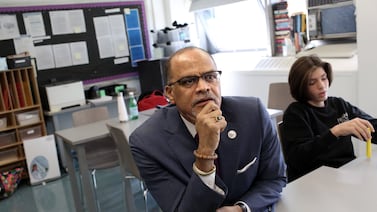

Board Vice President Auon’tai Anderson, a chief proponent of removing school resource officers back in 2020, said he was scared for his personal safety. Marrero expressed frustration that board members had not asked right away about the health of the two East High deans who were shot and injured the day before by a student who later died by suicide.

Denver Public Schools leaders fought for four months to keep the conversation private. Chalkbeat and other media organizations sued in April, alleging that the meeting violated the Open Meetings Act. A Denver District Court judge agreed and ordered the recording released in its entirety. DPS refused and appealed that decision, but on Friday, the school board voted unanimously to release a redacted version.

Chalkbeat reviewed the four-hour recording that was released Saturday to the media organizations through their attorneys. The audio quality is poor, and the sound sometimes cuts in and out. But the recording provides new insight into how and why the Denver school board initially decided to approve returning school resource officers to Denver campuses — a major policy reversal made unanimously with no public discussion.

The recording shows that school board members mostly treated the return of SROs as inevitable, even as several said SROs would not entirely solve the problem of gun violence.

Tensions flared at times, especially between Marrero and Anderson.

A few hours after the shooting on March 22, Marrero informed board members that he would return armed police officers to high schools in violation of board policy.

During the March 23 closed-door meeting, known as an executive session, some board members were upset about it — not necessarily about what Marrero had done, but about how he’d done it.

“The school board is the ones being blamed for this,” Anderson said of the shooting. “You’ve made yourself the hero. Everybody is applauding you. … We got the emails thanking you: ‘Go SROs! Go SROs! Thank you for your courage, Superintendent Marrero. But f—k the rest of the seven board members.’ Those are the emails: ‘Resign today.’”

Marrero said he acknowledged that Anderson, who co-authored a 2020 policy banning school resource officers from Denver schools, was bearing the brunt of the criticism.

But Marrero said he too was getting calls to resign, and that his decision to reinstate police in schools could have repercussions for his career as a superintendent.

“People are calling for my resignation because I am pro-cop all of a sudden,” Marrero said. “I have a career beyond this. Fifty percent of the districts won’t see me from here on out.”

Meeting redacted after question about legal liability

Only 20 seconds of the recording were redacted. The redaction involves a discussion of the Claire Davis Act, named for a Colorado student killed in a school shooting. The state law creates a legal obligation for schools to exercise “reasonable care” to protect all students, faculty, and staff from “reasonably foreseeable” acts of violence that occur at school.

In the meeting, a DPS staff member asked DPS attorney Aaron Thompson if the Claire Davis Act could “open the door” to school board members or Marrero being held liable.

“Yeah, it could,” Thompson said. “I don’t think we’re there yet based on the incident that happened at East.” Then the recording cuts out.

Throughout the meeting, board members said the community wanted SROs back.

“I think that the community is clamoring for SROs,” board member Carrie Olson said. “And we all know that is not the answer.”

Board member Scott Esserman said, “We can’t simply respond with SROs. It’s the easy response. It’s the convenient response. But it can’t be the only response.”

Board member Michelle Quattlebaum said that if DPS moved to bring back SROs, “it needs to be thoughtful. They can’t come back the way they were.”

Anderson repeatedly said the board’s hands were tied. Marrero had said former Mayor Michael Hancock told him he would issue an executive order to put police in schools. Because of that, Anderson said, “the decision has already been made without the duly elected school board.”

But at another point, Marrero implied Anderson was in favor of SROs. In a tense exchange, Marrero said that Denver Police Chief Ron Thomas told him Anderson had called Thomas after the East shooting and demanded Thomas put 80 officers in the schools. And Anderson himself said he had asked for SROs to return after East student Luis Garcia was shot in February.

A previous school board that included Anderson, Olson, and board member Scott Baldermann voted unanimously in 2020 to remove SROs from Denver schools amid concerns about racist policing and how Black students were disproportionately ticketed and arrested.

Baldermann came to the executive session with a resolution he’d drafted to temporarily suspend the SRO ban. The resolution backed what Marrero had said he’d do the day before, but it put the decision back in the school board’s hands, where board members said it should be.

“What I’m most interested in is that we as a board take action,” Baldermann said. “And I think the public is expecting us to take action as well.”

However, Baldermann’s proposed resolution sparked a lengthy debate about a wonky topic that dominated the executive session: whether the board was acting in accordance with policy governance, the governance structure that dictates how the board should operate.

Under policy governance, resolutions that order the superintendent to take a certain action are discouraged. Instead, the board is supposed to govern by setting policies and goals that the superintendent must follow and achieve. The board can also set limitations that spell out what the superintendent can’t do. At the time, there was a limitation — called executive limitation 10.10 — that said the superintendent could not staff schools with SROs.

Marrero argued during the executive session that the board passing a resolution would violate his contract, which said the board must operate using policy governance.

Board members questioned if meeting should be public instead

In the end, the board members decided to turn Baldermann’s resolution into a memo. They spent an hour and a half wordsmithing it, debating changes as small as whether to capitalize certain words and as big as whether to delete a sentence that implied “trained professionals,” and not school staff, would pat down students for weapons.

The East High student who shot the deans had a safety plan that required him to be patted down daily by an assistant principal. On the day of the shooting, the assistant principal wasn’t available and a dean had taken over, Marrero said.

Some board members said the phrase “trained professionals” implied that SROs would be patting down students. But a DPS attorney told them that wouldn’t be allowed unless the SROs had probable cause. The board ended up deleting the sentence.

The board held a brief public meeting when it came out of the session. Board members read the memo aloud and voted unanimously to adopt it without discussion.

Chalkbeat and the other media organizations sued on the basis that the board made a major policy decision behind closed doors, and that the meeting was not properly noticed. State law allows elected officials to meet in private for certain reasons, but says that the “formation of public policy is public business and may not be conducted in secret.”

The meeting notice said the executive session would cover confidential matters, specialized details of security arrangements, and information about individual students who would be harmed by the public disclosure of that information.

After listening to the recording, Denver District Court Judge Andrew Luxen found the school board’s discussion didn’t match the meeting notice, and that the board didn’t discuss any confidential matters. He ordered DPS to release the recording, but the district appealed that decision.

The recording reveals that board members asked at various times during the executive session whether they should be meeting in public instead.

“As we are talking about suspending policy, this conversation doesn’t need to be public?” Anderson asked DPS attorney Thompson at one point.

“I think what we’ll have to do is present this memo and then vote to suspend the policy,” Thompson said.

The board’s decision to temporarily return SROs kicked off several months of intense community and board debate about whether to keep SROs next school year, and whether Denver has the right safety and discipline policies.

On June 15, the board voted again to reinstate SROs — but that time, the debate was public and the vote was divided. Anderson, Esserman, and Quattlebaum voted no.

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.