With historic investments in K-12 education, the launch of universal preschool, and new policies to make college more accessible, many education advocates are hailing Colorado’s 2022 legislative session as a win for children, parents, and teachers during a time when schools are struggling to recover from the pandemic.

Even so, it will take time for many of the changes to be felt in Colorado classrooms, with some policies set to take years to implement and districts struggling to hire teachers, classroom aides, and bus drivers.

In many regards, education issues flew under the radar in a session that was dominated by emotional, high-stakes debates about addressing the fentanyl crisis and guaranteeing the right to a legal abortion.

One of the bigger education bills of the session laid out a pathway to resume school ratings based on standardized test scores, which have been on hold since the arrival of COVID in 2020. It passed with little fanfare or public debate. Education advocates said that was the work of months of behind-the-scenes negotiations.

Also happening off stage, education workers were removed from a controversial proposal to extend collective bargaining rights to more public sector workers. That dealt a blow to teachers and campus workers unions and meant relief to school districts and institutions of higher education.

The biggest splash was legislation laying out a detailed plan to offer 10 hours a week of free preschool for 4-year-olds by fall 2023 and moving early childhood and child abuse prevention programs into a new cabinet-level Department of Early Childhood. A marching band accompanied Gov. Jared Polis, who is up for re-election, to the signing ceremony, where preschool children played amid the gathered crowd.

“This was an incredibly transformative moment with the potential to change the lives of families with young children into the future,” said Melissa Mares, director of early childhood initiatives for the Colorado Children’s Campaign, who also pointed to $100 million dedicated to helping child care providers. “Our policy makers and leaders are really seeing the importance of caregiving.”

Republicans, who are in the minority, said this year was a lost opportunity to more meaningfully address low student achievement and give more rights — and public money — to parents. Nearly every bill in what they dubbed the “Commitment to Colorado” was defeated in Democratic-controlled committees.

Raising fears that it was unsustainable, Democratic leaders also rejected a Republican-led effort to increase K-12 funding even more in the state budget.

“With almost unchecked spending authority and billions of dollars at their disposal, the party in charge chose to prioritize the creation of new offices of government — an excess of green energy projects, in my opinion — instead of students in trouble,” said state Sen. Paul Lundeen, a Monument Republican, who specifically cited $65 million for electric school buses as an example.

But for Democrats, those kinds of investments represent good uses of one-time dollars that complement a broader education agenda.

“Once you purchase an electric school bus, it’ll save the school district money for a decade or two,” Polis said. “Rather than have money go to diesel fuel, it goes to pay teachers and reduce class size. There’s long-time benefit to these one-time investments.”

Jen Walmer of Democrats for Education Reform said lawmakers “focused on kids and schools and made long-term investments even with one-time money.”

In an election year when Democrats hope to maintain control of state government and Republicans seek to retake the state Senate, education debates from the session could reappear on campaign flyers and in robocalls.

Bret Miles, executive director of the Colorado Association of School Executives, said K-12 schools ended up with far more money than he expected going into the session.

“In other states, people were saying we don’t have to do anything because we have federal dollars,” he said. “We still saw our state make investments.”

Leslie Colwell, vice president of K-12 initiatives at the Colorado Children’s Campaign, said she was especially pleased to see the state chip away at long-standing inequities, increasing funding for special education, setting up a matching fund to help low property-wealth districts leverage local taxes, and changing how the state counts children in poverty. Many of these efforts were bipartisan.

The pandemic highlighted problems that had existed for decades and created more urgency to act, Colwell said. Even so, the legislature had limited ability to help.

“There is a lot of repair that needs to happen, academically and emotionally,” Colwell said. “We’re working at the state policy level on things that won’t be felt for a while. Kids need more right now.”

Here’s a look at key education legislation from the 2022 session and what it means for students, parents, and teachers.

More money for schools: Colorado lawmakers came closer to fully funding the state’s schools than at any point since the beginning of the Great Recession, when lawmakers started holding back money to pay for other budget priorities. Average per-student funding will go up 6% to $9,560, and lawmakers held back just $321 million out of more than $5 million in base K-12 spending.

Lawmakers increased special education funding 40% to $1,750 per student, an extra $80 million. The bill puts Colorado on track to meet promises made in 2006 and keep up with inflation going forward.

Lawmakers also committed to creating a more accurate way to measure students in poverty that doesn’t rely on applications for subsidized lunch, a prerequisite for changing Colorado’s nearly 30-year-old school finance formula.

They set up a matching fund to help school districts with low property wealth where voters agree to tax themselves extra, sent more money to charter schools authorized by the state that don’t benefit from district revenue-sharing, and made major investments in the youth behavioral health system.

Teacher evaluation reform: Student test scores will get less weight in teacher evaluations, and teachers who get consistently high marks will get less intensive assessments.

Many teachers and Democratic lawmakers favored a more extensive overhaul, but Polis was clear that he wanted to maintain some connection between teacher ratings and student growth, which will now account for 30% rather than 50% of a teacher’s evaluation.

Separate legislation suspends the use of student growth data until 2024, an acknowledgement that teachers are not responsible for multiple years of pandemic-disrupted learning.

More teachers and better instruction: Amid widespread staffing shortages, lawmakers passed two bills making it easier for retired teachers and other school workers to get back in the classroom without jeopardizing their pension benefits. Superintendents said it was one of the most helpful things to happen this year.

Another bill creates stipends for student teachers and extends student loan forgiveness to teachers who started their careers during the pandemic and stuck it out.

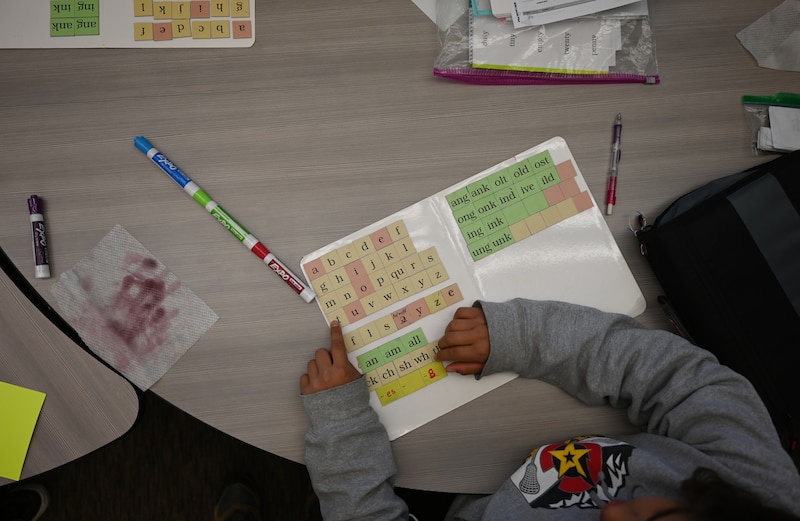

And continuing the state’s push to improve reading instruction, elementary principals and reading interventionists will have to take training similar to that required in 2019 of elementary teachers.

Rethinking school discipline: Colorado schools will have to share more information about school climate and student discipline, and the state education department will have to make that information readily accessible to families. Advocates hope the information shines new light on racial disparities in who gets disciplined most harshly and leads to larger changes, including more money for schools to address behavioral issues and better training for teachers.

The bill also sets higher standards for school resource officers and makes key changes to how schools handle restraint, placing students in physical holds, and seclusion, placing students in a secure room by themselves. School officials will now have to notify parents promptly if their child is restrained for a minute or more or secluded, and schools will have to share more information with state education officials.

Chalkbeat investigations in 2020 and 2021 found there was little oversight on the use of seclusion and restraint, and the state had little enforcement power.

Healthy students and schools: Lawmakers sent a ballot measure to voters to fund free school lunches for all students, picking up where pandemic federal support is going away.

Another bill requires lead testing and remediation in child care centers and schools that serve students through eighth grade. Home day cares can opt out of the program. The bill creates a dedicated fund with $21 million to cover the cost of testing, filters, and other remediation.

College access: Youth coming out of the foster system will have their tuition covered at public colleges and universities. Colleges will no longer be able to withhold transcripts to collect on unpaid fees or other debt, a move that could help thousands of students go back to school. More undocumented youth who graduate from Colorado high schools will qualify for in-state tuition, expanding a benefit that started in 2013. And a special committee will work on ways to help students with disabilities on campus.

Lawmakers also took steps to get more Colorado high school students to apply for federal financial aid. Every year Colorado students leave about $30 million in federal financial aid unclaimed. Legislation requires schools to tell students about the FAFSA as part of their individualized postsecondary plans and calls for the use of online tools to make filling it out easier.

But they stopped short of dramatically expanding access to college courses for free in high school. Instead, lawmakers commissioned a study of Colorado’s various extended high school programs, which have become a form of free college in a state that underfunds its higher education institutions.

Connecting college and career: Colleges will be able to tap $91 million in grants to develop new programs and partnerships that better align their programming with the needs of regional employers, part of a package of legislation that aims to help students and employers. Another bill creates programs to help students “stack” credentials, so that each semester or two translates into concrete progress, while a third requires better tracking of student outcomes so students can make informed choices and colleges and universities can improve their services.

Bureau Chief Erica Meltzer covers education policy and politics and oversees Chalkbeat Colorado’s education coverage. Contact Erica at emeltzer@chalkbeat.org.