A group of Colorado educators and advocates are raising concerns that the state’s new directives on reading instruction might harm one group of students who can’t afford to be left behind: those whose first language is not English.

Officials across the country have been following a new push to align reading instruction with science that shows students need direct phonics instruction in the early grades to learn to read.

But Colorado researchers who study strategies for English language learners say this push, and its research, have not specifically considered the needs of English learners. And they say that that while phonics instruction is important for all students, including for those who are learning English as a new language, teachers should not ignore other literacy components such as comprehension and oral language.

The group, Higher Educators in Linguistically Diverse Education, sent state officials letters this year explaining their fear that overemphasis on phonics for English learners will produce students who can fluidly pronounce words but lack the knowledge and vocabulary to understand what they’re reading.

The state’s 120,000 English learners make up about 13% of its K-12 students. In Colorado, 58% of third-graders don’t meet grade level expectations in reading and writing tests, and English language learners represent a disproportionate share of students identified as having reading difficulties.

“It’s easy to count and tally the sounds that students can make correctly,” said Peter Vigil, HELDE president and a professor in the school of education at Metropolitan State University of Denver. “Barking out sounds is not reading.”

There are five key concepts in learning to read, including phonics and phonemic awareness, which is the understanding that letters are associated with a sound and that certain sounds strung together form a word. The other components include vocabulary, reading comprehension, and fluency, which includes oral language skills.

A recent movement has criticized the way many teachers teach reading, arguing that the failure to explicitly teach phonics explains why many students don’t learn to read.

English learner researchers don’t dispute that those five key areas are important for English learners. But several in Colorado worry that the pendulum could swing to overemphasize phonics and ignore other areas.

They say that some areas such as comprehension are key for those learning the English language. It’s not enough to learn to decode the sounds of a word and pronounce it; they must know what those words mean.

Kathy Escamilla, a researcher on bilingual education at the University of Colorado Boulder and member of HELDE, says schools must provide both language development and reading instruction for English learners.

“My fear is these two things get reduced to decoding,” Escamilla said. “I’m afraid we’re narrowing a curriculum.”

Officials of the Colorado Department of Education defended the state’s new emphasis, telling the group, “this focus comes from statute.”

Lawmakers in 2019 called for an audit of how districts spend state money for reading instruction. The state now requires them to use science-based literacy curriculum.

Floyd Cobb, the state executive director of teaching and learning, said he doesn’t share the HELDE group’s concerns about English learners.

“I don’t have any evidence that students who are English language learners have been ignored” in the science of reading research, Cobb said.

He said that although it’s possible to imagine that some teachers could overcorrect and underutilize some components of reading instruction such as comprehension, he said that can be resolved by properly training teachers and doesn’t require undoing the systemic changes the state is making.

“The end goal in all of this is to make sure we’re supporting students to make sure they’re able to read, independent of whatever their native language is,” Cobb said.

The focus on phonics, and the concept that letters correlate to certain sounds, is something all students need, he said.

This year, the Colorado Department of Education released a list of approved reading curriculum resources for districts.

But the rubric used to review the curriculum materials, created by reading consultant Stephanie Stollar, mentions English language learners only once.

Despite that, Cobb said that the reading instruction rules will apply to all readers.

The state is still partway through reviewing Spanish-language reading curriculum.

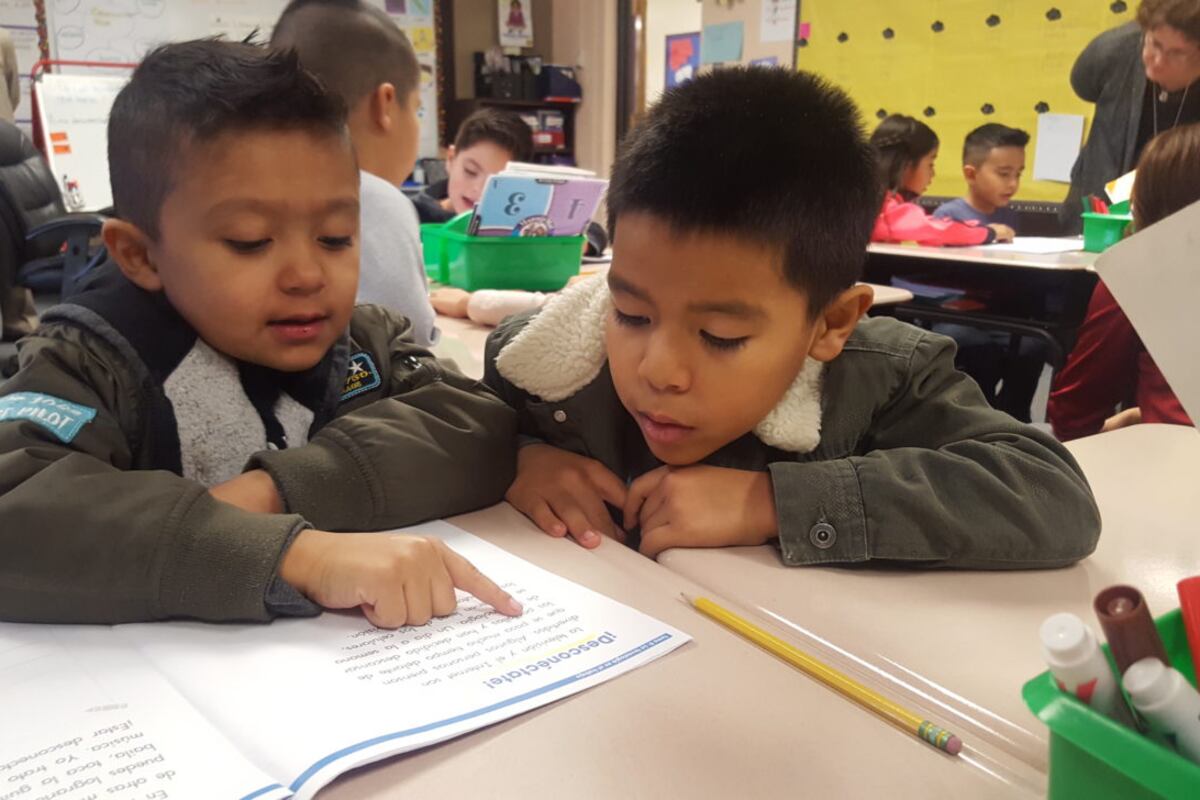

In Colorado, as in most other states, many English learners learn to read in English-speaking classrooms. Denver Public Schools, which has 29,000 English learners, offers a bilingual program that allows native-Spanish speakers to begin learning in Spanish and slowly transition to learning in English in higher grades.

While some other schools and districts offer similar programs — and in a handful of cases for other languages — it is more common for students to learn in English-only classrooms, while receiving help throughout the day to develop their English.

Colorado’s law doesn’t call out phonics instruction exclusively, but critics worry that the focus on phonics, its importance in the state’s curriculum review, and how this is all communicated, might push other literacy instruction aside.

Science of reading discourages telling kids to look at pictures as they try to guess the words they are supposed to be “decoding” to read. But researchers for English learners say pictures can help English learners understand, and remember, what they are reading.

Most of the members of HELDE are leaders in higher education, including those who train teachers, and some in institutions that have been ordered by the state to revamp their teacher training programs. Nationally, those academics have been particularly resistant to the science of reading changes.

But, Vigil, the HELDE president, said that members are not unwilling to change their programs, but instead worry about how future teachers will work with English language learners.

“We’re concerned that this overreliance on phonetic instruction really doesn’t prepare our new teachers adequately to work with emerging bilinguals,” Vigil said.

English learner “students can often keep pace” in pronouncing words correctly and fluidly, the letter argues. “However, in comprehension and writing development they often fall behind doing less well in reading and writing on standardized tests.”

In 2019, about 13% of English learners in third grade met or exceeded expectations on language arts tests, compared with about 46% of students who are not English learners.

Part of that is because the test is given in English, which, by definition, language learners don’t yet understand. But other measures also show problems that could demonstrate English learners have challenges in learning to read or that teachers and tests don’t accurately measure their skills.

Across Colorado, approximately 15.7% of students have been identified as having a significant reading deficiency. Among students who have some limited grasp of English, that portion is 21%, and among students who have no English proficiency, it is more than 42%.

Nationally, researchers find that English learners can be both under-identified and overidentified for reading problems. It can even vary from one school district to another.

Jorge Garcia, the executive director of Colorado Association for Bilingual Education, also has concerns about Colorado’s approach. He said that there are multiple reasons some data show poor performance for English learners, and he doesn’t blame it on a lack of phonics.

“They are attributing all of their poor test scores on one element of instruction,” Garcia said. “They think they have found the silver bullet. The moment you do that and you focus strictly on one thing, you’ll lose a group of readers.”

Kim Manning Ursetta, an early childhood teacher in Denver, has taught English learners from preschool to fifth grade for 27 years.

She said curriculum materials have never quite been adequate for bilingual teachers.

“Teachers have to do a lot to put it together,” Manning Ursetta said.

In the lower grades, when native Spanish speakers in Denver are learning largely in Spanish, she said that phonics instruction is important, and something that she has seen missing from some curriculum materials in the past.

For that reason, she said, teachers need flexibility to modify curriculum plans.

“It can’t be a one-size-fits-all solution,” she added.

Another factor that isn’t being considered in this reading debate, she said, is whether materials are culturally relevant.

Students need to read books and passages that are relevant, she said. Students need to “see themselves in the books,” she said. “You really have to know your students, know their backgrounds and use their strengths to help them learn.”

A lot of research on students who are learning English as a new language looks at the benefit of bilingual programs that let students use foundations from their native language as they learn English.

Steve Amendum, a professor at the University of Delaware’s School of Education, recently co-authored a study that tracked students whose first language was Spanish as they moved from kindergarten through fourth grade.

Students who began kindergarten with stronger beginner skills in reading in Spanish, such as recognizing the alphabet or having some phonics awareness, eventually showed more growth in English reading. Those early Spanish reading skills made more of a difference than how well they spoke English at the start of kindergarten. It shows the importance of taking advantage of a student’s skills in a native language, he said.

But, “those things aren’t typically incorporated into the science of reading principles,” Amendum said.

He said the way the science of reading research gets translated into policies or classroom practice leaves important elements behind.

“It’s a narrow band of findings from the larger body of reading research; however, I don’t disagree with them. Kids absolutely need to be automatic decoders, yes that’s true,” Amendum said. “But it ignores some of the other research that’s out there.”

Another researcher outside of Colorado, Diane August, said research on English learners has increased in recent years, and shows that they need the same literacy skills as native speakers with additional support. She agrees with HELDE’s points.

“English learners need to acquire the same literacy skills as English proficient kids,” August said. “They just need additional support when they are acquiring literacy in their second language. Educators should also take advantage of the literacy and language skills they may have acquired in their first language.”

For their part, the letter authors say that the state may be able to alleviate their concerns with small tweaks so that bilingual efforts and English learners don’t suffer. But they want to be involved in helping shape new direction.

A legislative group last year recommended that by last October, Colorado should “engage a work group of practitioners and experts in the fields of second language acquisition, literacy,” and others to provide guidance on how to identify “significant reading deficiencies” in English learners and to develop methods for teaching for emerging bilingual students. The state has not created that group.

Melissa Colsman, associate commissioner of student learning for the education department, said that the department will follow through, but officials are waiting for an external review of the state’s practices due next summer.

Colsman said the department has engaged with English learner experts for creating guidance in the past, but hasn’t done so recently.

Escamilla pointed to New Mexico as an example of collaboration among state leaders, local experts, and advocates to change the state’s reading approach. There, the state’s reading changes will include a framework for biliteracy, a model that emphasizes equal reading and writing proficiency in two languages.

David Rogers, who is involved in that collaboration, said leaders are happy to be talking.

“We need to get people with biliteracy development expertise… to see where there’s alignment and where there needs to be a respect for biliteracy development,” said Rogers, executive director for the nonprofit Dual Language Education of New Mexico. “We all just need to talk more about this.”

This story was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.