Georgia O’Keefe’s paintings of animal skulls flash on an overhead projector at Polaris at Ebert, the only stand-alone magnet school for gifted students in the Denver Public Schools.

Second-graders study the pictures and the curved antlers on tables in front of them and sketch their own O’Keefe-inspired masterpieces as sunlight pours through windows with views to downtown skyscrapers.

“What do bones represent?’’ art teacher Danny Mey asks the 6- and 7-year-olds. “Let’s look again at O’Keefe’s work.”

Hands shoot up.

“Animals. Skeletons. Pets,” students answer. “Death,’’ says one boy.

“That’s right,’’ says Mey, known as Coach D. “And what are you studying right now?”

Several children answer at once: “The Day of the Dead.’’

Polaris integrates the arts into nearly every aspect of its curriculum and knits “specials” like art, music, drama and library with thematic studies in core academic classes. Second-graders study Latin America. During the fall, their journey takes them to Mexico. With excitement building over Halloween, October is the perfect time to ponder the spookiness of the Day of the Dead tradition.

On this particular Monday morning, a tour group of more than a dozen prospective parents strolls through the classroom during Coach D’s O’Keefe lesson. The parents are spellbound.

One mother, Ashley McCollum, a former gifted teacher at a DPS school in Stapleton, has brought her 8-year-old, Casey, to see if the school’s a good fit for him. His 6-year-old sister is a first-grader at Polaris.

McCollum, who is home-schooling Casey, is a big fan of the Polaris program.

“I love that it’s art-infused. I love the thematic units, the integration of all subjects. Children need to see connections,’’ she said.

“Highly gifted” means application, tests

While she’s enthusiastic about the program and DPS’ gifted offerings, she sees complications with its application and testing demands.

“If you’re not in the loop, you can miss out,’’ McCollum said. “And there are issues with the testing. I don’t think everyone is gifted in the same way. A child could be gifted artistically or gifted academically.’’

Being “in the loop” has been especially challenging this year. The deadline to apply for Denver’s Highly Gifted and Talented magnet program, known as HGT, for next fall was moved up to Oct. 22. Last year, the deadline was in November and, two years ago, it was in December.

The result is that parents and teachers need to plan a year ahead to give their students a chance to qualify for the program.

Polaris Principal Karin Johnson is concerned about the earlier deadline and its potential impact on her efforts to improve diversity.

Polaris’ ethnic breakdown is nearly the reverse of the city district. Last school year, 79 percent of Polaris students were white compared to 25 percent of all DPS students. The income gap is even greater: 71 percent of DPS students were eligible for federal lunch aid in 2009-10 compared to 11 percent of Polaris students.

Ethnic imbalances in gifted programs

Imbalances are not new in gifted programs across Colorado. In 2004-05, white students made up 64 percent of statewide enrollment but accounted for 75 percent of all gifted students. Conversely, Hispanic students were 26 percent of statewide enrollment and 15 percent of gifted students.

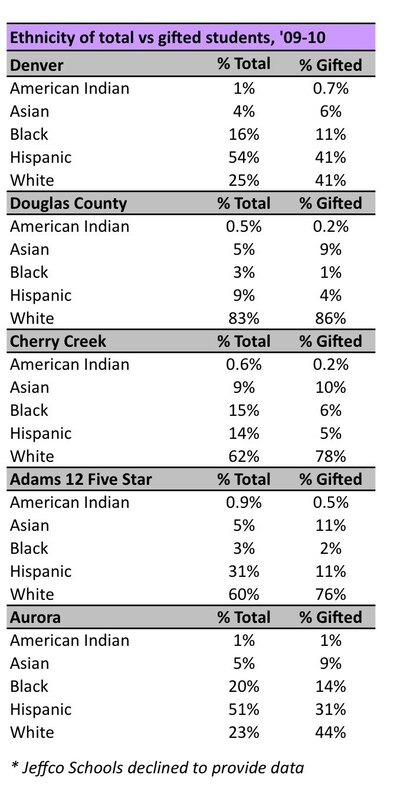

Click on graphic to enlarge.

Such imbalances persist in 2009-10 in some of the state’s largest districts, according to data obtained under the state’s Open Records Act by Education News Colorado.

For example, in Douglas County, Hispanic students were 9 percent of total enrollment and 5 percent of those identified as gifted. In Adams 12 Five Star, white students were 60 percent of total enrollment and 76 percent of gifted students.

And in Cherry Creek, black students were 15 percent of enrollment and 6 percent of gifted. Jefferson County Public Schools, the state’s largest district, declined to provide any data, saying staff would not be available until December to pull the numbers.

Denver Public Schools’ follows the trends – white and Asian students are overrepresented in gifted programs while Hispanic, Black and Native American students are underrepresented.

Hispanics were 54 percent of all DPS students in 2009-10 and 41 percent of all gifted students. Whites also were 41 percent of gifted students but make up just 25 percent of total enrollment.

Denver’s HGT program further skewed

DPS’ numbers are further skewed when HGT numbers – the very top performers among the gifted – are separated from all gifted numbers. Looking at HGT only, white participation shoots up to 75 percent and Hispanic participation drops to 13 percent.

Click on graphic to enlarge.

A key difference between HGT programs such as Polaris and regular gifted programs in DPS is that getting into HGT, like any magnet program, requires an application by a parent, teacher or relative.

All DPS students are assessed in grades 2 and 4 to determine their gifted potential. Those scoring at or above the 90th percentile on the test are identified as gifted. Those students can then apply for the HGT program or receive services in their home schools.

Getting into HGT is more complicated. Students must apply for the program, then score at or above about the 97th percentile on one of various tests that measure spatial, math or verbal abilities. This year’s Oct. 22 application deadline is followed by a testing window in November.

Once in HGT, students can choose from eight magnet elementary programs, including Polaris. Several elementaries offer “schools within a school,” where an entire classroom is devoted to gifted education. At other schools, gifted learners mix with typical students in the same classes.

And families can elect to stay at their home school. In that case, teachers who specialize in gifted education pull children out of class or work with regular teachers to give the children more advanced work.

Gifted, and under the radar

At Farrell B. Howell ECE – 8 School in northeast Denver, near I-70 and Peoria, teacher Sandi Eckert specializes in providing gifted education to children who might otherwise fall under the radar.

Eckert recalls one native Spanish-speaking child who arrived in preschool and quickly learned English. In kindergarten, he was reading at a beginning first-grade level. By the end of the second-grade, he had zoomed up to a level comparable to a beginning fourth-grader.

Eckert and the boy’s teacher were amazed that he jumped four grade levels in just two years. They helped the family apply for HGT designation and started providing creative projects to stimulate his hunger for knowledge.

For instance, they gave the boy a project on solar systems. He built his own 3-D model of the solar system and did extra space activities.

“You want to give them a productive choice. Instead of giving them more work sheets, you want to give them options so they can do projects and activities that stimulate them, challenge their thinking and help them grow,’’ Eckert said.

Typically, gifted students love to read, are exceptionally curious and are great problem solvers, she said: “I’ve had kids get on my case if they don’t have enough homework.”

When language is a stumbling block, Eckert and teachers will sometimes work with English-speaking siblings to help fill out the HGT application form in either English or Spanish.

Even if the child qualifies for the HGT magnet program, Eckert finds some families feel anchored to their home schools.

“I’ve had parents ask me, ‘Do we have to go to the assigned school?’ ’’ Eckert said.

Community outreach at Polaris

Johnson, the Polaris principal, has worked over the past two years with Metro Organizations for People, a community advocacy group, in an attempt to boost diversity at her school. She has marketed the program to parents and community leaders in surrounding downtown neighborhoods.

Still, on her packed weekly tours, white parents often dominate.

A former actor before becoming a teacher and principal, Johnson leads the tours with dramatic flair.

She shows off the giant book-filled library and raves about the school’s spacious classrooms. Art projects line the hallways. The kindergarten classroom has its own mini zoo, courtesy of veteran teacher Eileen Wise, who brings tarantulas, hedgehogs, snakes and chickens to school.

Johnson gives parents specific instructions on the application process, urges them to download the application right away and carefully follow the instructions.

Then she closes the deal.

“Please join us. There is an urban legend that you cannot get into Polaris,’’ Johnson said. “If your child doesn’t get in for kindergarten, do try again. Every year, we add an entire first grade and an entire grade in the upper levels, typically in the fourth grade.

“We’d love to have you and your children here.”

A ‘tricky dance’ in DPS

Ann Laros-Weaver is another teacher who came for Johnson’s tour recently. She happened to hear about the earlier deadlines this year. Her husband has been working in Dubai and she hopes her two children will be able to get in to Polaris for second and fourth grades next year.

Laros-Weaver used to teach preschool at a low-income Denver school where she was stunned to find her young students conversant on topics such as the difference between jail and prison.

No doubt, the school had its share of gifted children. But it was unclear to Laros-Weaver whether the parents could or would apply for special programs for their children.

“I think it’s very daunting for some families. I advocated in the past for some of my students to apply. For some of those folks, just downloading the application is tricky,” Laros-Weaver said.

She understands DPS must support both its brightest children and those who are struggling.

“It’s a tricky dance. Not everyone needs the same thing. They’ve got to nurture everyone,’’ she said.

Despite that conflict, Laros-Weaver hopes the district will continue to foster, and if the demand grows, expand its HGT magnet programs.

“Polaris is a gem. They should nurture this,’’ she said. “I love the creativity and the imagination at Polaris. I want my children to see diversity. I also want something emotionally safe and intellectually inspiring.”

Fast facts about DPS’s Gifted and Talented offerings:

- GT – Gifted and Talented. This designation is given to students without any application. All second- and fourth-graders in DPS are given the Raven’s test. Children who score over about the 90th percentile are labeled GT. They can then apply for the HGT magnet program or receive services at their home schools. About 8,000 children a year are identified as GT.

- HGT – Highly Gifted and Talented. Parents, teachers or relatives apply for children to participate in the HGT magnet program in Denver. The magnets include eight elementary schools and one middle school. Students who qualify typically score at or above about the 97th percentile on the Raven’s or CogAt tests – assessments commonly used for gifted identification. About 1,600 students applied last year and about 200 qualified.

- HGT magnet sites – “School within a school” model (gifted classrooms within the school): Archuleta, Carson, Edison, Gust and Southmoor elementaries; Morey Middle School. Integrated model (gifted children mixed with typical children): Cory and Teller. Gifted magnet school: Polaris at Ebert.

- Learn more – DPS’ Gifted and Talented web page. Colorado Department of Education’s Gifted and Talented web page.