State test scores released Tuesday show little change in the numbers of children able to read, write or perform math at grade level.

For the third straight year, 68 percent of Colorado students in grades 3 through 10 were reading at proficient or advanced levels. In ten years, that number has moved little. In 2001, when the first reading exams were given across that grade span, 64 percent of students were proficient or advanced readers.

What’s newer about Tuesday’s results is the ability, based on Colorado’s growth model, to predict how many students deficient in the basic skills will catch up in the next three years or by the time they finish grade 10.

The answer: Not many.

For example, just under half – or 45 percent — of test-takers achieved proficiency in math on the exams given in spring 2010. How many will catch up? The state predicts fewer than one in five.

In real numbers, that means 133,750 students across the state will still be behind in math in three years’ time.

About 35 percent of struggling readers are expected to catch up – leaving 74,276 pupils behind. And 24 percent of struggling writers are likely to catch up – meaning 106,863 will not.

Schools and districts across the state are trying a variety of experiments to improve those odds. Education News Colorado analyzed state test results around several reform efforts to see what’s working:

Aurora Pilot Schools

Patterned after a successful initiative in Boston, these Aurora schools exchange greater freedoms for greater accountability.

Principals in pilot schools are given greater control over budget, instruction, time and staffing and are expected to demonstrate significant increases in achievement within three years.

Click on charts to enlarge – click again to reduce.

William Smith High School, which became the first pilot school in August 2008, is seeing gains, particularly in reading. Fletcher Elementary, which split into primary and intermediate schools in its pilot form, is not.

Fletcher has just one year of scores in its pilot form – its combined reading and math scores in the two new schools are 3 to 6 points lower than the scores posted by Fletcher Elementary in 2009.

Pilot schools are expected to outperform district CSAP average. Smith made it in years one and two – it already was closer to that goal than Fletcher when each became pilot schools. Fletcher has further to go.

Growth in Harrison

EdNews analyzed ten years’ worth of reading results to determine which of the state’s largest 20 school districts were making sustained progress over time.

The analysis also included the ten Colorado districts with more than 5,000 students and poverty rates topping 50 percent.

The standouts? Denver Public Schools and Harrison District 2 in southeastern Colorado Springs. (See related DPS story here.)

Click on graphs to enlarge.

The two were the only large urban districts making double-digit increases in reading proficiency between 2001 and 2010. Both reported gains of 12 percentage points.

For comparison’s sake – the state’s gain was 4 points, Douglas County schools gained 1 point and Aurora Public Schools dropped a point.

It’s unclear what growth may be tracked to the myriad of reforms initiated by Superintendent Mike Miles, who took over the 10,776-student district in 2006.

Reading proficiency grew by five points between 2001 and 2005 and another seven points between 2005 and 2010.

In addition, between 2005 and 2010, Harrison students have posted 10 point gains in math and five point gains in writing. The statewide proficiency rate has gained four points in math and dropped a point in writing.

Results are not yet in on Miles’ ambitious overhaul of teacher pay in Harrison, which has drawn national attention from education watchers – and concern from some teacher groups. It kicks off this fall.

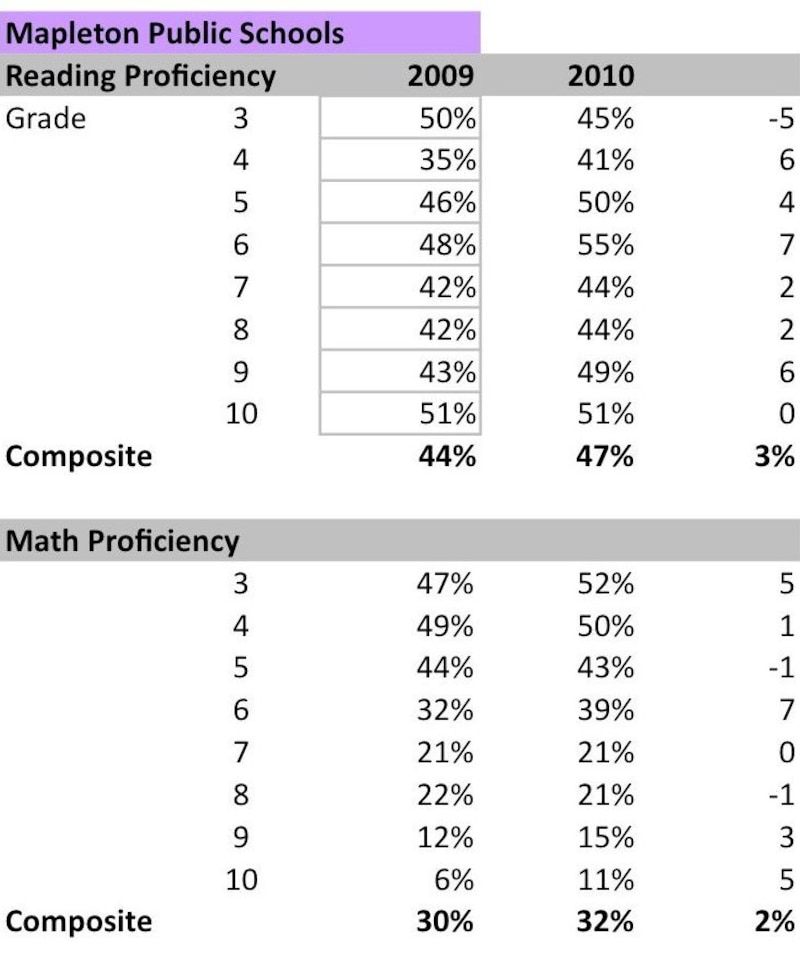

Mapleton’s choice

The small district north of Denver with the big reform plan appears to have turned the corner on growth.

In 2005, Mapleton Public Schools began the radical shift from a traditional district of neighborhood schools to an all-choice model – parents must pick a school for their child.

Click on graphs to enlarge.

The gradual evolution from several large schools to 17 small ones was followed by more losses than gains on the annual state exams.

A $2.6 million grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation helped fund the reform and national attention was focused on a plan that seemed to be heading south.

But last year, that trend reversed and it’s holding steady for 2010. The 5,401-student district saw gains in reading and math though writing scores dipped, as they did statewide.

All that change has played out against a backdrop of demographic flux – Mapleton’s poverty rate has climbed from 38 percent in 2001 to 54 percent in 2005 to 70 percent in 2009.

“We believe we are seeing the gains we were hoping for five years ago when we reinvented the school district,” said Jackie Kapushion, the district’s assistant superintendent, who sees proof in the results that small schools work.

“The amount of growth is pretty close to last year,” she said. “To have two consecutive years of high growth is very meaningful. When you see the stair-step growth that we see in a lot of grade levels, it tells us that our programs and the consistency in implementation is working.”

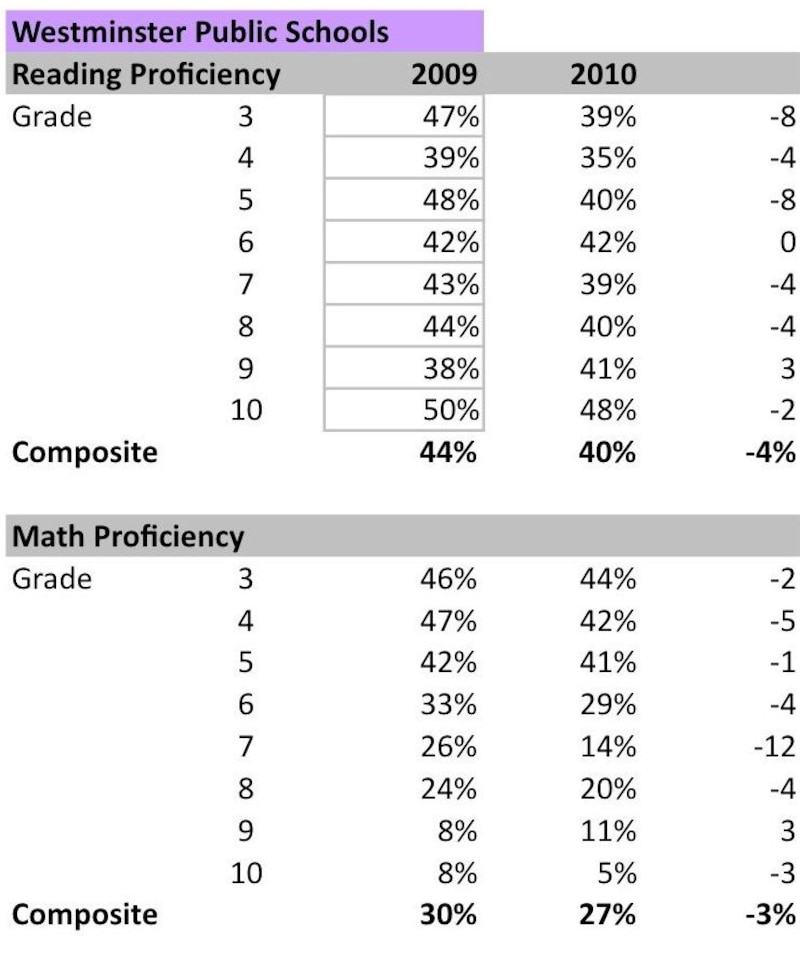

Standards in Westminster

Like Mapleton, its neighbor to the east, the Adams 50 school district in Westminster has grappled with demographic upheaval.

Its poverty rate nearly doubled, from 39 percent to 76 percent, between 2001 and 2010. During that same ten-year span, its overall reading proficiency level has dropped seven points.

Click on graphs to enlarge.

Last fall, the district took dramatic action by scrapping grade levels and letters grades in favor of grouping kids by ability. Students progress through ten academic levels based on their mastery of subjects, not how long they’ve been in school.

The standards-based education model has been tried in parts of Alaska and in some individual schools – but never in an urban district of 9,371 students.

Results after year one of the change show a continued slide in reading, writing and math. Scores fell on all but three of the 24 tests given in grades 3 through 10 in those subjects.

Fewer than 30 percent of Westminster students scored proficient or advanced on state math and writing tests this past spring. Forty percent were proficient or above in reading.

Roberta Selleck, who has led the district since 2006, said the drop in scores was expected and she, her staff and community remain committed to the reform plan.

“The CSAP scores were as predicted, even though it still didn’t feel good to see the actual results,” the superintendent said.

Because students in Adams 50 aren’t grouped by traditional grade level but by ability, she pointed out, some who lag behind may not have seen what’s covered on the CSAP prior to taking the test.

Selleck said one school, Metz Elementary, which piloted the standards effort in 2008-09, has seen gains and made Adequate Yearly Progress under the No Child Left Behind Act.

“We are hopeful that, as we continue, that will be our trend,” she said. “We’re staunch supporters of our reform. There is absolutely no indication that we would ever look in the rearview mirror.”

Nancy Mitchell can be reached at nmitchell@ednewscolorado.org or 303-478-4573.