Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to keep up with education news from Denver and around the state.

Many adults fear that, at some point, the skills they have spent years mastering may suddenly become obsolete.

My father, an art teacher and darkroom aficionado, railed against digital photography in the early 2000s as the downfall of an art form he held (and still holds) dear. He retired before the transformation of his darkroom into a classroom computer lab and many years before the revival of film photography from Gen Z kids seeking authenticity in the smartphone age.

In 19th-century England, Luddites similarly protested textile machinery by famously smashing the expensive devices. Their outcry captured the imagination of many who feared that we were becoming, as the Victorian writer Thomas Carlyle put it, “mechanical in head and heart.”

As someone who loves to write almost as much as I enjoy teaching students how to do so effectively, the arrival of Chat GPT in my Denver classroom last semester has placed me in a similar predicament. Within a few weeks, everything I knew about writing, plagiarism, student accountability, and grading was tested.

I made a number of mistakes in a short time, and I realized that if we continue to treat the use of AI as plagiarism, we’re all doomed to fail. Instead, we need to question the fundamentals of how we teach writing in high school and examine what we’re grading when we read student writing.

“What’s the point of writing anymore if we now have browser extensions to do it for us? I mean, why am I even teaching this?” I asked my tech-worker friend when I was at my lowest. “Writing as we know it is dead!”

“Not exactly,” he said, explaining that because AI relies on human-created content to generate answers, it, therefore, depends on the creativity of humans to improve. Otherwise, it would be a closed system that continued to get dumber over time. Moreover, he predicted that as AI content becomes ubiquitous, human creativity would be essential for work to stand out in the future.

“Still,” he acknowledged, “it’s going to change writing a lot.”

Midway through grading student research papers in May, I began to realize what he had meant. I began clumsily pasting suspicious sections of various essays into Chat GPT and asking, “Did you write this?” I’m embarrassed at the number of random false positives this method generated and the awkward conversations I needlessly had with students.

“Yes, I wrote that,” the AI would respond.

“Are you sure?” I pressed further.

“Apologies for the confusion, I cannot confirm that I wrote it.”

After several days of the slowest grading of my life, a colleague introduced me to a browser extension that would confirm patterns in the writing that seemed to be AI-generated. Sure, students could edit the writing to avoid detection, but that seemed quite extreme and time-consuming. I was later surprised to learn from students that some of them would, indeed, spend far longer than it actually takes to write an essay editing AI-generated content.

I found myself spending so much time looking for cheating that I missed the most important aspect of my grading: the ideas that students were actually coming up with.

It was reassuring when an essay I was grading received a thumbs up and “A Human Wrote This!” message. But what is a teacher supposed to do when a browser extension says that an essay appears to be “87% human”? Plagiarism often comes with stiff penalties, and I was nervous about responding too strictly to such uncertainties. This dynamic is also playing out in higher education, and none of the professors I reached out to had answers yet.

This past spring, I found myself spending so much time looking for cheating that I missed the most important aspect of my grading: the ideas that students were actually coming up with. As I shifted my focus, I realized that centering the student’s ideas also proved to be the best AI detector of all. Because AI writing is often pretty terrible.

I began grading some of the best AI-generated essays as though they were human, and I realized that they were rarely proficient anyway. A lot of their issues were obvious, such as the research essay on the history of the American West that intermittently (and critically) confused which “West” it was writing about — the Cold War West or the Western frontier.

There are also some practical ways I intend to alter these projects next year. For example, typing into one document ensures that all writing is timestamped. Separately grading the research process, outlines, and rough drafts all help to encourage students to do the thinking themselves. The inner Luddite in me is also excited to return occasionally to handwritten essays.

Most of all, though, I’m eager to emphasize creativity in research and writing. Classroom writing should never be about the regurgitation of other people’s ideas to aid memorization, and I’m fairly certain that this is one skill that AI will truly make obsolete anyway. So rather than asking students to “Compare and contrast how two authors explore the history of the American West,” I might instead ask them to “use primary sources you have found during your own research to tell the story of a real person in the West, including their challenges and life experiences.” Certainly, AI could do this, but results are certain to be duller than those that tap into students’ natural curiosity and creativity.

This tumultuous semester clarified that using AI in writing is fundamentally different from other forms of plagiarism; it’s so new that the line between using it as a research and writing aid and using it to cheat has not yet been established. I’m optimistic that we can teach students to use it as a tool while they simultaneously do the most valuable creative thinking themselves.

In recent years, my dad has emerged from the darkroom to embrace digital photography as an art form with its own creative potential. And I’d like to think that if Thomas Carlyle was alive today, he would have agreed with me that it’s the creativity of our thinking that separates us from machines; AI in its current form merely develops an illusion of creativity.

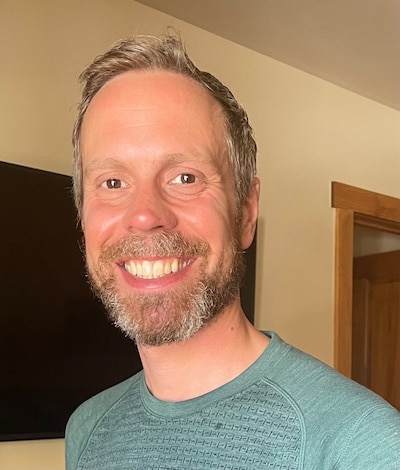

Matthew Fulford is a high school history teacher in Denver, Colorado. His passion is teaching historical research and writing. He is the 2023 Colorado History Teacher of the Year.