It has long been part of my job as a school administrator to listen to parents with complaints, but there was something different about the first half of this school year. Everyone seemed mad.

My child’s teacher is picking on her.

My daughter is being bullied on social media, and the school needs to make it stop.

The school dismissal plan is violating my son’s rights.

During my years as an educator, I have come to expect such complaints. Kids have always had big feelings about being teased or getting in trouble, and many parents reach out to the school for help. In a typical school year, we have one or two parents of our more than 1,000 students who get so frustrated that they talk to me, the Executive Director, or complain directly to the school district.

But during the first half of this school year, I found myself fielding complaints almost weekly, and most of the time, the parent hadn’t yet spoken to the teacher or the principal before escalating the concern. This still represented a tiny percentage of our parents, but the shift felt meaningful to me.

The change, I think, has everything to do with how families experienced school these past few years. That’s because schools are built on relationships. When we are disconnected from each other, it’s harder to trust and work through challenges. Due to COVID restrictions, we were in little Zoom boxes or waving to parents through car windows at dismissal for over two years. Until just recently, we’d canceled all our in-person events. Some parents hadn’t even been inside the school building where they were leaving their little 5-year-olds each day.

As we lost connection, our school became every school — the faceless bureaucracy people complain about on social media and in the news. We were no longer the people who care about your child. We were no longer the people you talk about sports, weather, and traffic with as you stand around at the back-to-school potluck or wait for the music performance to start.

Some parents hadn’t even been inside the school building where they were leaving their little 5-year-olds each day.

We were able to maintain some semblance of connection the first year when so many of us were stranded at home, but since then, and this year especially, connections have frayed.

All of us adults are struggling right now. For two years, we worried about catching a new and potentially deadly virus. Schools closed and sent us all home, which is something that has never happened in our lifetimes. When you are stressed and living in a state of fear, your brain floods your body with hormones meant to prepare you for fighting or fleeing. It spikes your blood pressure and sends energy to your muscles. It primes you for action. Over time, it becomes harder to respond with the appropriate level of emotion. Everything still feels like an emergency. Maybe this is also why, across the country, we are seeing more rage — on the road, in workplaces, on airplanes, in restaurants, and at schools among children and parents alike.

We are a trauma-informed school, meaning our staff has been trained in how to support children who have experienced trauma. We know that being calm, consistent, and clear helps children when they get dysregulated. We now know from brain science that when children experience trauma, it makes it harder for them to respond appropriately to stress. A slight disagreement with a friend or not getting the marker color they want triggers their fight-or-flight response. They can’t help it. But we can help them learn how to calm down their body with deep breaths. We can help them use their words to express how they are feeling. We can reinforce behavior expectations and teach them what they should do instead. We know that building caring relationships with our students helps, too.

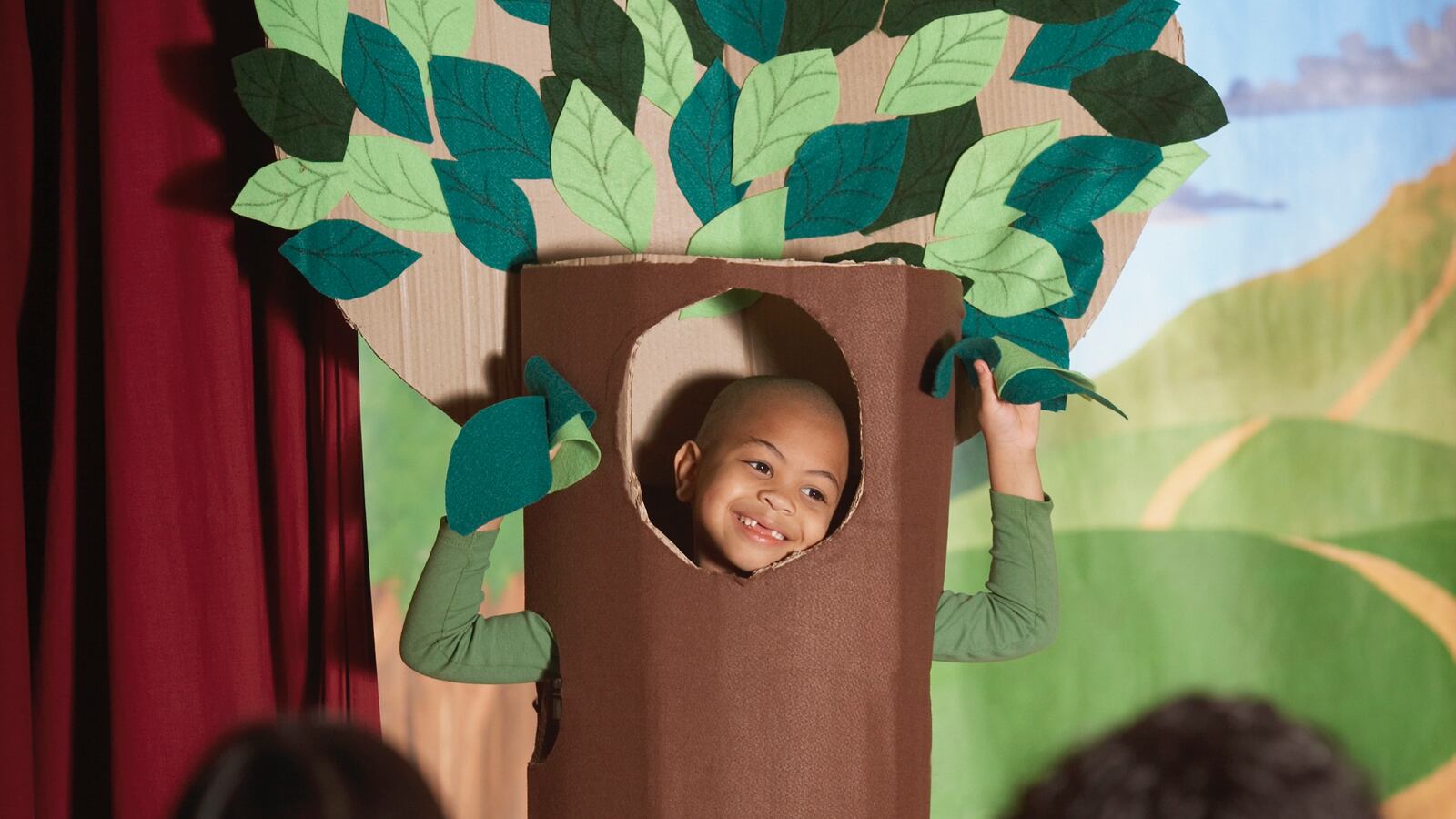

Since the end of March, we have been able to start bringing our parents back into our building. We started small with a few tours for enrolled families who had never been inside and our multilingual learners performing “Stone Soup” and other fables for their family members. This month, we are bringing back assemblies, in-person parent-teacher conferences, and a spring festival.

Communities are created through small rituals like these, and our community is beginning to mend. I haven’t had a parent complaint escalate to the district since spring break. Next year, we have a new principal starting at one of our schools who has a passion for community events. She is excited to invite families to performances, potlucks, kindergarten breakfasts, and PTA meetings. School events help connect us, parents to educators, and parents to each other. As we emerge from a period of sustained trauma, we all need a village.

Who knew so much depends on a school potluck?

Christine Ferris is Executive Director of Highline Academy Charter Schools in Denver. She founded and led Our Community School, a K-8 charter school in Los Angeles from 2005 to 2013. Ferris has been a consultant for multiple charter schools in Denver, Los Angeles, and nationally.