Charlie Windy Boy was one of dozens of students, parents, and community members who pleaded with the Denver school board Monday night not to close the American Indian Academy of Denver, a charter school that is struggling with low enrollment and funding.

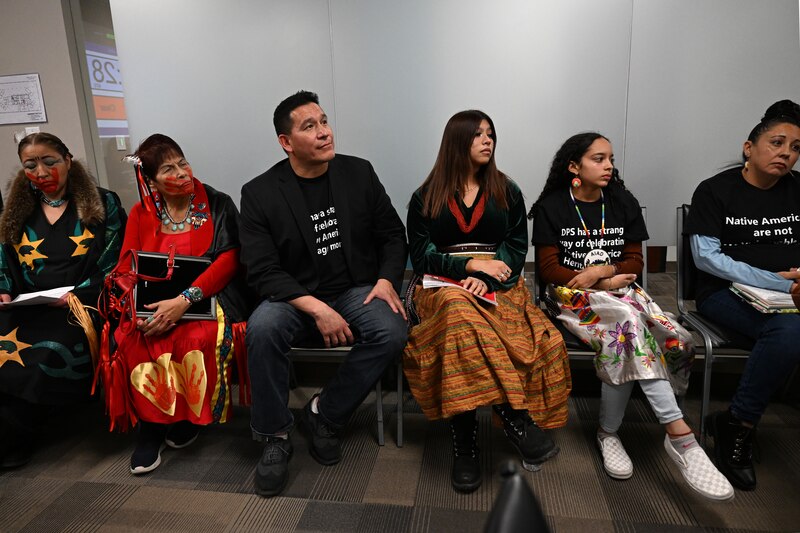

Native American students told stories of being bullied in their previous schools but not at AIAD. They introduced themselves in Navajo and Lakota, and their parents spoke of the power of restoring those languages to their families. Community members wore black T-shirts that said, “DPS has a strange way of celebrating Native American Heritage Month.”

“You already took our land,” Windy Boy said. “Why are you trying to take our school?”

AIAD supporters were at the meeting because district officials have said they’re considering the unusual step of revoking the school’s charter for educational and financial reasons, including that the school may run out of money. But Superintendent Alex Marrero said he was “flabbergasted” by the demand to save the school when he hadn’t yet recommended closing it.

AIAD was planning more advocacy Tuesday, on the anniversary of the Sand Creek Massacre, with a rally featuring officials from five tribes whose ancestral homelands are now Colorado.

“The advocacy is always welcome but, quite frankly, it’s premature because no one is deliberating on a closure,” Marrero said. He apologized to the school board for what he called “misguided” comments from the speakers. “I do want to apologize to this board that there’s been accusations that you all are considering closure when I know that you’re not.”

Because AIAD is a charter school, Marrero said the responsibility for its struggles lies with its independent governing board, not the district. He suggested that even if AIAD lost its charter, the district could provide the same type of education in another school.

“This school is not going to disappear, folks,” he said. “It may look different in the future.”

But students repeatedly spoke about how other public schools hadn’t worked for them, how teachers had ignored them or told them to cut their long hair. The meeting was tense at times, with Marrero asking anyone to stand up if they’d heard him say he wanted to close their school.

“No one is going to stand up,” a man in the audience said.

“Because it never happened,” Marrero said.

AIAD opened in the fall of 2020, just months after the start of the pandemic. It was founded to educate Native American students, who have long been underserved by the district.

But halfway through its third year, the school is struggling with low enrollment and funding. Charters are funded per pupil, and AIAD has just 134 students in grades six through 10.

In an interview with Chalkbeat earlier this month, Grant Guyer, the district’s chief of strategy and portfolio services, said Denver Public Schools is considering revoking AIAD’s charter, though district officials have not yet formally recommended it.

The school board authorized AIAD’s charter and would have the final say in revoking it. AIAD’s contract runs through June 30, 2024, but the board can vote to revoke the charter at the end of any semester for several reasons, including financial insolvency.

If AIAD doesn’t raise $428,000 by January, it will run out of cash and be unable to make payroll, according to a “notice of concern” the district issued the school last month.

That notice cites other concerns too, including low student test scores, high turnover of special education staff, and a high percentage of students leaving the school midyear last year.

But the students and parents who spoke Monday night described the school differently. Ruby Cardenas said her eighth grade son, a gamer and football player who “does not wake up for anything,” wakes up at 6:30 a.m. every day to take the bus to AIAD.

Ninth-grader Sa’mya Black Calf said that in her previous schools, she was called racial slurs and taught that Native Americans were extinct. At AIAD, she said, she’s participated in traditional buffalo harvests and helped bring indigenous knowledge to state parks.

“AIAD has shared how amazing and how much I love my culture, how I should embrace it and not be embarrassed by it,” Black Calf said.

Students said AIAD’s curriculum is like nothing they’ve been taught before. The school’s founder, Terri Bissonette, describes it as an “indigenized” curriculum focused on science, technology, engineering, art, and math, which is abbreviated as STEAM.

“We learn about real world topics without all of the sugar coating,” ninth grader Isabelle Estrada said. “We learn the ways of our ancestors before us. We learn about our culture and how beautiful it is. Here, we don’t have to be ashamed of where we come from.”

Bissonette acknowledged that AIAD has struggled with enrollment. Opening during the pandemic was hard, she said, and the mental health challenges experienced by some students had a profound impact on the school. But she took issue with how AIAD has been treated by district officials, including Marrero, who sent an email blast to all district families laying bare the school’s problems after supporters gave similar testimony at a meeting last month.

That email caused three AIAD staff members to resign, Bissonette said. On Monday, she pushed back on Marrero’s assertion that AIAD was not threatened with closure, saying district officials had laid out several options, including that AIAD close on its own or be closed by the school board — options that Marrero said were “news to me.”

“We have it in writing,” Bissonette said.

A memo to AIAD from district officials dated Nov. 4 says the most viable options are that AIAD relinquish its charter or the school board revokes it. The memo says AIAD could consolidate with an existing school or reopen as a district-run school but notes those options aren’t realistic, according to a copy obtained by Chalkbeat.

AIAD is not the only Denver school struggling with low enrollment. Still, the school board has been hesitant to close small schools. Less than two weeks ago, the board rejected a recommendation from Marrero to close two district-run schools — Math and Science Leadership Academy and Denver Discovery School — with fewer students than AIAD. Another small school, Montbello Career and Technical High School, was spared from closure last month.

A dozen charter schools with low enrollment have voluntarily closed in the past four years. Last month, homegrown charter network STRIVE Prep announced it will close its 188-student Lake middle school campus at the end of this school year.

But it seems unlikely AIAD will do the same.

“We are American Indian Academy,” said student Shawna Talk, holding back tears, “and we are staying and we’re not going to go anywhere.”

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.