This story originally appeared in the Ouray County Plaindealer.

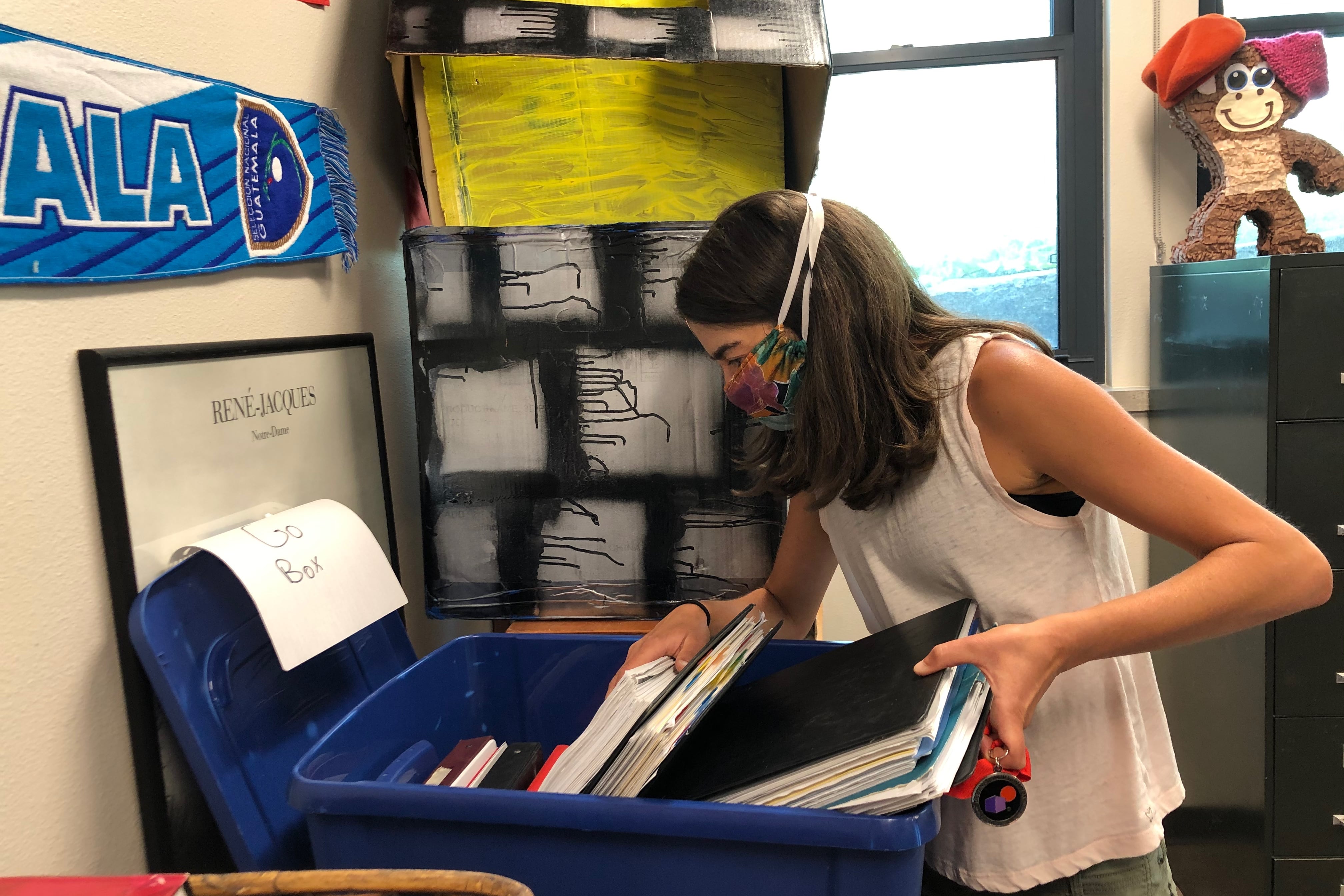

As she reassembled her classroom at Ouray School last week, high school teacher Taylor Chase was planning for two realities.

She arranged photo albums and books along the windowsill, ready for students to return and flip through the pages, and tried to visualize how her desks would be set up to meet spacing requirements for in-person French and Spanish classes.

But as she prepared to return to her classroom, she also made plans to leave it again. One of her first tasks was to pack up a blue plastic bin, labeled “go box.” It’s filled with the books and binders of curricula she’ll take home if they move back to online classes.

Signs of this spring’s unplanned, chaotic shutdown, when classes moved online without any time to prepare, filled the school last week as teachers returned for training and to ready their classrooms. One calendar was still set to March, with spring break still on the horizon.

“The world turned upside down since the last time people were in here,” Chase said.

In some rooms, desks were already arranged with the mandatory spacing between them; in others, teachers worked to reorganize their rooms, trying to balance minimizing high-touch surfaces with keeping their classrooms familiar and welcoming.

In the hallway, trash bags and boxes filled with stuffed animals and pillows waited to be put in storage, alongside soft armchairs.

Teachers have removed many of those items from their classrooms, replacing them with easy-to-clean rubber stools and foam pads. Preschoolers will have their own assigned stuffed animals, and throughout the elementary school, students will keep their own supplies in cubbies and desks instead of sharing.

“No sharing in first grade” will be an unusual approach, teacher Jenny Anesi said. But with only 13 students expected in her classroom, she’s optimistic about making it work, after previously teaching in a larger district.

She recently added a few books about masks and social distancing to her classroom library, a way to familiarize her students with the new norms. “We’ll just go with it,” she said.

Melissa Cervone gestured around her second grade classroom at the changes: individual desks for each student, no bean bags or camp chairs, a box of LEGOs that will need to be divided into individual bags for each student to use. There are plenty of details still to determine, like passing out take-home folders for students.

“I honestly can’t get my head around it without trying it,” she said.

Cervone is expecting more changes during and after the first week of school, when teachers will be able to meet and re-evaluate their plans.

“I don’t know how it’s going to play out,” preschool teacher Monke Hazen said.

At that age, her students are typically learning about things like washing their hands and covering their sneezes, so they’ll be “learning about safety within their routines.”

She’s used to cleaning up and wiping down the classroom regularly, she said, though this year it will be even more frequent.

For the younger grades, some of the new normals of social distancing are hard to imagine, teachers said. If a student is crying, it’s not realistic to think a teacher won’t hug them, Anesi said.

Throughout the school, several said they’re planning to be outside as much as possible, weather permitting.

Hazen is planning for nature hunts and games outside on the playground and on the walkway outside her classroom.

Chase bought a portable whiteboard to use outside or to hold class in the park nearby. Usually, class outside is a treat, but this year, they’ll do it “until it’s too wet and too snowy,” she said.

Inside, teachers said they’ll have their windows open to maximize ventilation, as long as the weather allows.

Armed with the new guidelines from the state and the school, teachers said they feel more prepared for an unusual year than this spring, but some of the logistics of day-to-day lessons are still up in the air.

“I have no idea what to expect,” high school math teacher Scott LeStage said. “We’re more prepared,” but so much is still unknown about how the fall semester will go.

Some of the changes might be positive beyond the pandemic, like the new high school schedule, he said. They’ll have fewer, longer class periods each day, which was implemented to cut down on movement between classes, but LeStage thinks it will also help students focus more on each subject.

“Can you really flip your mind through eight subjects a day and dig deep in any one?” he asked.

With only five periods, there will be more time to cover material during class, and it may reduce stress, LeStage said.

He’s less sure about how other aspects of returning to class will look, including social distancing and using the online system.

“I’m not worried, but there are things I feel like I can’t answer,” he said.

For some, there’s still a lingering question of “are we doing the right thing?” high school science teacher Beth Lakin said.

She’s not too worried about spacing out students, with plenty of room in her classroom and lab to alternate students if needed, but she’s wary of how much she’ll have to enforce some of the new regulations.

“I don’t want to be the mask police, the distancing police,” Lakin said. “I want to be your teacher.”

She’ll have conversations with students about following the restrictions so they’re able to stay in school, but otherwise, she isn’t planning to talk much about the virus in her science lessons.

“There’s so much fatigue about talking about it,” she said. “Maybe when I have this year’s third graders, with some distance, to talk about how things evolved.”

Moving online at some point feels inevitable, Chase said, even with the district’s precautions. One of the “silver linings” of her experience this spring, though, was finding a good rhythm for virtual classes and seeing what worked in that setting.

This year, “I can build the class knowing it might happen,” she said. “It’s hard, but I’m preparing in my mind, these are the tools I’ll have to pull out.”

While the school will be making efforts to keep students in separate cohorts to minimize contact, that’s not possible to enforce outside of school.

Cervone said that will come down to communication with families, “to let them know that these efforts won’t be worth the effort and time put in if they go outside and gather in large groups.”

The highest risk of transmission, according to guidelines from the Colorado Department of Education, comes from contact between adults, or adults and older students, while younger children likely play a more limited role in spreading the virus.

Cervone is already making plans for how she’ll try to mitigate the chance of bringing home the virus and infecting her family. She’ll put her clothes straight into the laundry and shower before interacting with her family, an effort to protect her husband, who is disabled, she said.

Chase compared returning to the classroom to a trip she and her husband took to visit family this summer.

“I feel the same way as when I got on a plane,” she said, wearing masks and sitting away from other passengers. “I’ve taken every single precaution but it doesn’t necessarily make it safe.”

“It will be hard, and scary, especially as people get sick,” even with just a common cold or the regular flu.

“We’re in a small enough community and enough thought has been put in. There will be hiccups but I don’t see a situation for us like we went through in March,” LeStage said.

Liz Teitz is a journalist with Report for America, a nonprofit organization with a mission of supporting quality journalism in underserved areas.