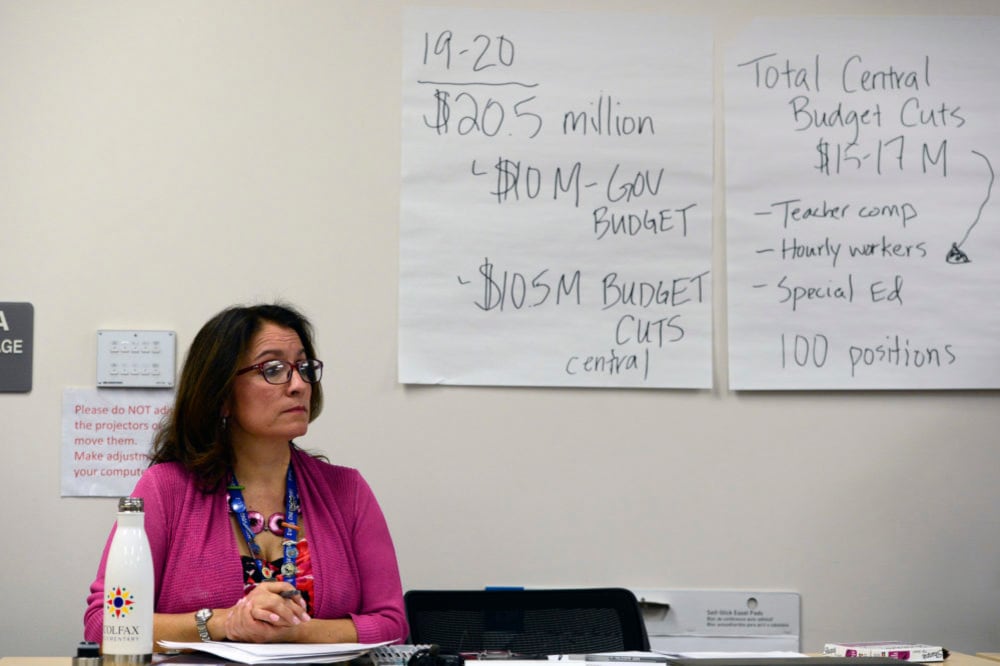

Faced with having to cut tens of millions of dollars from the school district budget next year, some Denver school board members are asking questions about the size of the district administration and just how much the superintendent shrunk it last year to pay for teacher raises.

After a three-day teacher strike, Superintendent Susana Cordova said she would cut $17 million and 150 positions from the Denver Public Schools central office. The district did cut millions of dollars in staff positions and saved millions more through consolidating different functions.

But skepticism about the depth of the cuts has remained. Many central office employees were rehired into new jobs, sometimes with higher pay, as part of a broader reorganization. Critics who long accused the district of being top-heavy don’t think enough has changed.

The issue has gained urgency as the coronavirus decimates the Colorado economy. School districts are bracing for steep decreases in state education funding next year, and the Denver school board is discussing drastic budget cuts, including possibly freezing teacher pay.

“Unless we can get this cleared up, it’s going to overshadow everything we do with the budget,” school board President Carrie Olson said of the central office cuts.

Denver Public Schools is Colorado’s largest school district, and it operates on a $1.1 billion budget. A Chalkbeat analysis based on historical data found that Denver had more administrators than the statewide average in the 2016-17 school year and had gotten more top-heavy over time.

The Denver teachers union went on strike in February 2019 for higher wages and a different pay structure. They won both. Cordova, a former teacher who’d been hired as superintendent just a month earlier, vowed to cut from the top to pay teachers.

By June, the school board approved a budget for this school year that included $17 million in cuts from the academics division of the central office and an increase of $53 million in school budgets, most of it for teacher salaries, according to documents provided by district finance officials.

Almost immediately, teachers and community members began checking whether the district had done what it said. Retired Denver teacher Margaret Bobb, in particular, filed several open records requests in search of information about the administrative cuts. She spent over a year analyzing the data, and recently posted her findings on social media.

Bobb compared a list of people whose jobs were cut to a list of people who currently work in the central office. She found that more than 90 administrators who were cut are still there. In addition to getting new jobs and titles, she found that many of them got raises.

All in all, Bobb calculated that the staff cuts were less than $17 million. She found that the salaries of the central office employees who left the district for good added up to just $6 million. Other central office employees whose salaries accounted for $4 million got jobs in schools as teachers and principals. Total staff cuts to the central office added up to $10 million, she found.

Already distrustful of the district, Bobb said her findings only further cemented that belief.

“They claim they’re poor, they claim they’ve streamlined, they claim they’ve cut, and they’re giving each other raises down in the executive level,” Bobb said.

Bobb’s salary data is correct, and her count of employees is close to the district count. But district officials said her analysis doesn’t account for other savings that add up to more than $17 million.

In the end, Denver cut the equivalent of 117 full-time positions from the central office, said Jim Carpenter, the district’s chief financial officer. That number is lower than the 150 positions originally cited because some people worked part-time and other positions were funded by grants. Cutting 117 positions from the district’s general fund saved $10.8 million, Carpenter said.

Another $6.9 million in cuts came from savings other than district salaries, officials said.

The central office cuts were part of a bigger administrative reorganization by Cordova, who made streamlining the organization one of her objectives. For instance, she collapsed several departments in the academics division into one.

Those changes resulted in sizable savings, said Chuck Carpenter, the district’s executive director of finance. Instead of rolling over the previous year’s budget, each streamlined department started at zero and built a budget from there. Certain third-party contracts were canceled, and fewer employees meant less money allocated for travel, technology, and copying.

The first statement a district spokesperson made about the cuts in February 2019 mentioned streamlining. “We will consolidate or realign central office teams to align with Superintendent Cordova’s vision and core beliefs and eliminate redundancies in our work,” it said.

But while the cutting of positions got a lot of attention, including from central office employees who felt vilified by the call to cut them to pay teachers, the non-salary savings did not.

A department-by-department comparison of the 2018-19 and 2019-20 budgets recently prepared by district finance officials and provided to Chalkbeat shows the changes.

But that document wasn’t available at the time. Instead, district officials summarized the budget changes in slide decks they reasoned were more understandable for the general public.

“We thought it was more digestible to move to the more summarized schedules,” said Chuck Carpenter. But he acknowledged that sharing more detail is sometimes necessary: “The more that folks question things, the more you need to get into the raw detail.”

Board members have been frustrated by how difficult it’s been to sort this out — and at least some of them still have questions about how Bobb’s analysis compares with the district’s explanation. Olson said she spent the better part of a recent Saturday trying to understand it.

“I have a Ph.D. in quantitative research. I sat here and I thought, ‘I don’t get it,’” she said.

“At the end of the day, I don’t believe that the people in the budget department are trying to pull a fast one on us,” Olson said. But when she started digging into which positions were cut, she said she found herself wondering, “Is this really what we intended?”

Olson and board Vice President Jennifer Bacon said Bobb’s detailed analysis drew their attention to aspects of the reorganization that hadn’t been as clear before, including that, on average, lower-paid central office workers were laid off while higher-paid administrators were hired back into new positions as part of Cordova’s reorganization.

As the board looks to slash what could be as much as $60 million from next year’s budget in the face of decreased state funding, it has enlisted the help of a budget advisory committee made up of teachers, principals, parents, and community members. While further cuts to the central office weren’t initially identified as a possibility, the district is now listing it as an option.

“What we spend money on is a demonstration of our values,” Bacon said. “Have we seen what we want to see from that investment? That, for me, is what this whole conversation has opened up.”