With polite smiles firmly pasted on their faces, Colorado’s higher education leaders and bureaucrats are steeling themselves for an intense six months of work on a performance funding system that none of them asked for.

The work ahead seems wearily familiar to many in higher education, which in the last five years has gone through creation of a state strategic plan, the launch of a complex but temporary change in tuition policies, the passage of an earlier performance funding and master plan law and finally the negotiation of performance contracts between colleges and the state.

Through all the hours of meetings and in reams of documents, politicians and policymakers have largely been of one mind about Colorado’s higher education goals – increasing student retention and graduation rates, improving remedial education and reducing the state’s wide demographic gaps in college attendance, retention and graduation.

At a time when the state’s K-12 system is being challenged to increase the percentages of minority and at-risk students who graduate high school and go on college or vocational training, those same students lag behind white students in every key higher-education indicator – enrollment, need for remediation, staying in school and graduating.

Behind those educational and social goals is anxiety that Colorado will lose ground economically if the state doesn’t get more of its residents through college.

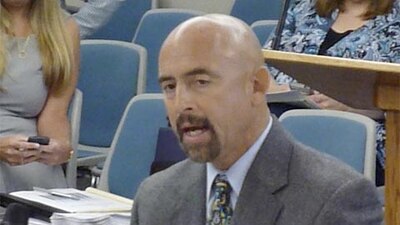

Now higher education will have to modify existing plans to achieve their goals, thanks to House Bill 14-1319. A pet project of outgoing House Speaker Mark Ferrandino, the bill easily passed both houses, but not until after the Denver Democrat made significant changes to the measure after pushback from the Colorado Commission on Higher Education (CCHE) and college leaders.

Ferrandino, long frustrated by the lobbying and deal-making that marked higher education funding decisions, also wanted to inject more transparency and predictability into the system. The speaker had lined up a long list of both Democratic and Republican cosponsors, and once he made his concessions in committee the bill sailed through both houses with little debate.

Key changes in the bill gave the Department of Higher Education and CCHE a greater role in designing some details of the new performance funding system, a task that will consume much of the rest of this year.

Ask people in higher education about the new law, and the word you frequently hear is “frustrating.” As one person involved in the legislative negotiations put it, “It’s somebody else’s vision. It’s not being built from the ground up.”

Frustrating or not, the ball now is in higher education’s court. “It’s yours now, you own it, it’s not somebody else’s,” DHE lobbyist Chad Marturano told the commission at its June meeting. (Marturano has since the left the Department to work for the University of Colorado System.)

Inside HB 14-1319

Simply put, the new law gives greater weight to enrollment and would base a modest – but still to-be-defined – amount of funding on institutional performance measures such as graduation and student retention.

But the law is anything but simple. “The complexity is pretty intense,” notes Mark Cavanaugh, DHE chief financial officer.

State support of higher education comes from two sources, the resident student stipends (basically tuition discounts) provided by the College Opportunity Fund and direct support of institutions known as fees for service. In the past there’s been little differentiation between the two sources, as total funding has fluctuated (mostly down) based on state revenues and has been allocated to colleges based on formulas negotiated by the institutions and DHE and rubber-stamped by the legislation.

(Colleges and universities will receive $604 million in operating funds from the state in 2014-15, up $90 million from 2012-13 but still below the 2008-09 high of $706 million. Statewide, about three-quarters of campus revenues come from tuition.)

The new law requires 52.5 percent of total funding be devoted to COF stipends. That would drive more funding to higher-enrollment institutions and is expected to most benefit Metropolitan State and Colorado Mesa universities and the community colleges. However, the law does allow adjustments when actually enrollment in the fall doesn’t match projections done when state budgets are approved in the spring, theoretically allowing stipend funding to drop below 52.5 percent in some years.

Fee-for-service funding will be distributed on the basis of institutional characteristics (admissions selectivity, enrollment, rural or urban character, number of graduate programs, etc.) and on the extent of services to low-income and first-generation students, plus two additional factors to be determined by CCHE.

Performance funding would be awarded for student retention and graduation, plus up to four additional factors decided by CCHE.

The law merely requires that fee-for-service and performance funding be “fairly balanced” – a needle that CCHE will have to thread.

There are separate provisions in the law for funding of specialty education programs, such as medical training at CU and for various CSU programs, and for regional vocational schools and non-state junior colleges.

The law also includes provisions to moderate excessive funding swings for institutions through 2019-20 and a way to suspend the system if state funding drops significantly.

The race to December

Timing is a key challenge, Lt. Gov. Joe Garcia told Chalkbeat Colorado in a recent interview. No other state has created such a plan “in this time frame,” he noted. “It’s a very abbreviated process.”

Kachina Weaver, a former legislative staffer who’s been hired to coordinate the process, agrees that it’s “an incredibly condensed time frame.” But, she added, “I don’t think it is unrealistic at all.”

The commission was briefed on the project earlier this month, and the law was discussed at a meeting of campus finance officers last week. College and university presidents are to be briefed at a session this week.

DHE staff members are developing a “foundational working document” about implementation for CCHE members to consider during a retreat in July, while August and September will be taken up with interest group meetings and collection of financial data.

An advisory committee including representatives from both higher education and the broader community will review the plan before the commission makes its final decision.

A final financial model is supposed to be selected by early December, with the whole package presented to legislative committees before Christmas.

If everything goes according to plan, the new finance system will go into effect for the 2015-16 school year.

The bottom line

“Everyone seems to understand we have to work on this together,” Cavanaugh said of how college leaders are reacting to the process.

But he and others acknowledge that discussions may get more difficult as the financial models are developed.

“They want to know what this is going to mean to their institutions,” he said. Weaver also noted that the thought of divvying up state funding in a new way “makes everybody a little uneasy.”

And without consensus on the plan, noted commission member Monte Moses, “we’ll be reliving this over and over” in future legislative fights over the funding plan, he said.

The biggest financial problem may be the state’s relatively meager support of higher education in recent years.

“The challenge is we don’t have enough money to fund all the things we want to do,” Garcia said. “To help one school means there’s less money to help another.” The lieutenant governor, who also heads DHE, is especially concerned about what happens in years when state funding drops. “We don’t know what money is going to be available the year this goes into effect.”

Tuition is the elephant in the room when college leaders gather to discuss funding. Tuition has risen steadily as state funding has dropped, and now legislators are pushing back. Another law passed this spring limited tuition hikes to no more than 6 percent in each of the next two years.

Tuition isn’t part of current HB 14-1319 planning – but the department and the commission have to produce a report on future tuition policy by Nov. 1, 2015.