At 8:40 a.m. on a recent Wednesday, students at Alsup Elmentary School in Commerce City converged on the cafeteria to pick up red and blue coolers filled with oranges and cartons of milk. As the students dispersed, pulling the wheeled coolers behind them, an aide filled a cart with hundreds of individually-wrapped sausage biscuits. These would also be delivered to each of the school’s 25 classrooms shortly before the 9 a.m. bell.

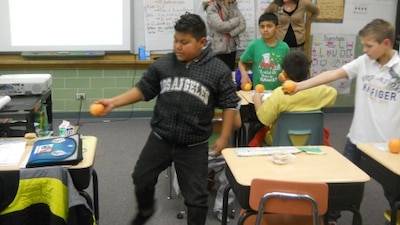

Once the bell rang and students came in from the playground, breakfast was ready. In teacher Rachel Freggario’s fourth grade classroom, three student helpers quickly distributed the food. Then students quietly peeled oranges and munched on biscuits while they worked on a persuasive essay about whether they’d want to move to Alaska.

This is how “breakfast after the bell,” which is free to all students, unfolds every day at Alsup in the Adams 14 district.

“It’s a really great start to the day,” said Freggiaro. “They’re more focused.”

Alsup Principal Teresa Benallo said, “It’s nothing we even talk about anymore. It’s part of our morning routine.”

It’s a routine that many more schools may have to adopt if House Bill 1006 is signed into law. The bill, which is currently under consideration in the legislature, would require schools to offer breakfast after the start of the school day if 70 percent or more of their students are eligible for free or reduced-price meals. Schools would have the flexibility to offer breakfast in the classroom, in the cafeteria or in another format.

According to Hunger Free Colorado, there are just over 380 schools in the state that would fall into the 70-percent-and-above category, and also meet the bill’s enrollment requirements. Around 100 of those schools already offer breakfast after the bell and would not need to make any changes, according to Jill Kidd, co-chair of the public policy committee for the Colorado School Nutrition Association and director of nutrition services for Pueblo City Schools. The remaining schools would have to make changes to their breakfast programs by the fall of 2014.

The debate about breakfast economics

Although no one seems to disagree with the idea of ensuring more low-income children start the day well fed and ready to learn, some food service directors have raised concerns about the cost.

They worry the new breakfast programs won’t break even as intended unless the free and reduced-price threshold in the bill is raised to 80 percent. Supporters of the bill, which include health, education, agricultural and business organizations, say increasing the threshold to 80 percent will prevent more than 61,000 low-income children from having access to a healthy breakfast every day. They also say that even at the 70-percent threshold, districts should be able to make money on breakfast after the bell, bringing in more money in federal and state meal reimbursements than they are spending to make the breakfasts.

In Adams 14, which provides breakfast-after-the-bell at all 13 schools, the food service department is on track to have a $1.6 million surplus from its breakfast program this year, said Nutrition Services Manager Cindy Veney. Districtwide, 83 percent of students are eligible for free or reduced-price meals.

The economics of universal breakfast programs are based on several factors, including the proportion of low-income and higher-income participants at each school, the reimbursement rates for each population, breakfast participation rates and “plate costs,” or the per-meal cost of making breakfast.

Colorado schools are reimbursed $1.85 for each free or reduced-price breakfast they provide, but only 27 cents for each breakfast they provide to a student not eligible for the price breaks. Supporters of the bill say plate costs should be $1.25-$1.35, but opponents say those estimates are low.

Kidd, who has heard concerns about costs from 10 districts, said plate costs will be closer to $1.56 when the bill takes effect. That means it will take four free and reduced-price meals to offset the cost of one meal provided to a “full-pay” student, she said.

“We’ve all run a lot of data and it pretty much comes to a break-even project when you go up to 80 percent.”

Maura Barnes, a policy analyst for Hunger Free Colorado, said a comprehensive financial analysis done by the bill’s supporters found that the 70 percent threshold is “more than doable.”

Mona Martinez-Brosh, director of nutrition services for Aurora Public Schools, fears her department will lose money and have to borrow from the district’s already-stretched general fund if the law passes.

“If you leave it at 70 percent we need some additional funding to run the program,” she said.

Martinez-Brosh currently offers breakfast after the bell in 12 district schools, and all but three have more than 80 percent of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunches. The nine “over-80 percent” schools help cover the costs of the three “below-80 percent” schools, she said.

“We know there are wonderful benefits,” Martinez-Brosh added.

For example, she said tardiness has decreased and students no longer go to the nurse’s office for symptoms related to hunger.

Weighing before-the-bell programs

Many schools that would be required to implement breakfast-after-the-bell programs if Bill 1006 becomes law already offer breakfast programs 20 or 30 minutes before school starts.

The problem is that participation in these programs tends to be low, with many low-income students missing out because they can’t get to school early enough or because they skip it for fear of being stigmatized as poor.

Aurora offers breakfast before the bell in 37 schools right now. On average, only 20 to 30 percent of students participate, as compared to an average of 77 percent at schools that offer breakfast after the bell.

Veney, of Adams 14, said she switched the district to breakfast in the classroom after observing a before-school breakfast program unfold at one of her elementary schools three years ago. A kindergartener and her third grade sister came into the cafeteria five minutes before the bell rang. After sitting down with bagels, milk and juice, an aide began to yell at them to hurry up and told the younger sister to put back her juice. While the older sister crammed the bagel into her mouth as fast as she could, tears streamed down the younger girl’s face.

“It was horrible to watch,” Veney said.

A couple months later, she piloted breakfast in the classroom at one elementary school. By the fall of 2010, all district schools switched to breakfast after the bell. While Veney understands concerns about the 70 percent threshold, she believes it’s important to have the force of law behind breakfast after the bell.

“If it’s mandated, those two little girls are never going to have to go hungry.”