Alexander Ooms is a member of the board of the Charter School Institute, West Denver Preparatory Charter Schools and the Colorado chapter of Stand for Children.

Jeannie Kaplan and Andrea Merida, two sitting members of Denver’s board of education, published this Op-Ed last Friday. Its genesis, they tell us, is in their conversations with Denver parents. “We are listening,” they write, “and are calling for the truth about how neighborhood schools perform.”

The specific call follows a few paragraphs later:

“But the data are clear that neighborhood middle schools are exceeding the growth expectations of the Denver Plan. These schools are actually performing better than the district average, including all the newer schools.”

Well, no. Pretty to think so. But not true. Traditional middle schools in Denver are lagging the district average for academic growth, not leading it. And more often than not, their students graduate 8th grade lacking the basic skills necessary to be successful in high school and beyond.

We are now over five years into the Denver Plan and a serious civic conversation about public education. So perhaps we might raise the bar just a little: It should not be okay for elected school board members to selectively choose and distort performance data, and then use it as a basis to recommend where parents should send their children to school. And that is exactly what these board members are doing.

A deceptive bouquet

Let’s look, for a moment, at the edifice of reason on which the authors build the claim that traditional middle schools “are actually performing better than the district average.” The evidence, we are told, rests on some impressive data on the academic growth of students in traditional middle schools:

- Hill Middle School in central Denver posted a whopping 38-point gain in eighth-grade reading.

- Grant Middle School in southeast Denver experienced a 10-point jump in sixth-grade reading.

- Henry World School in southwest Denver posted a 9-point gain in seventh-grade reading.

- Skinner Middle School in northwest Denver posted a staggering 23- point increase in sixth-grade writing.

These are terrific results. But there are several problems, of which we need chose only the most obvious: They cite exactly four examples. Four data points — each from a single grade, in a single subject, in a single unspecified year and from a different school. Four data points, each plucked delicately as a flower, bundled exquisitely together, and presented as a shimmering bouquet of truth.

But the Denver Plan was adopted back in 2005. In the past three years alone, these four schools each have three subject scores per year in each of three grades. That makes a total of 108 individual scores — 108 flowers growing in a field, from which the authors selected a total of, um, four (or 3.7 percent).

Now, choosing four out of over 100 of anything means one is either highly sophisticated, or really selective. So when the authors say that traditional middle schools “are actually performing better than the district average,” might it be that their delicate arrangement of four data points is not a representative sample of the truth for which they are calling?

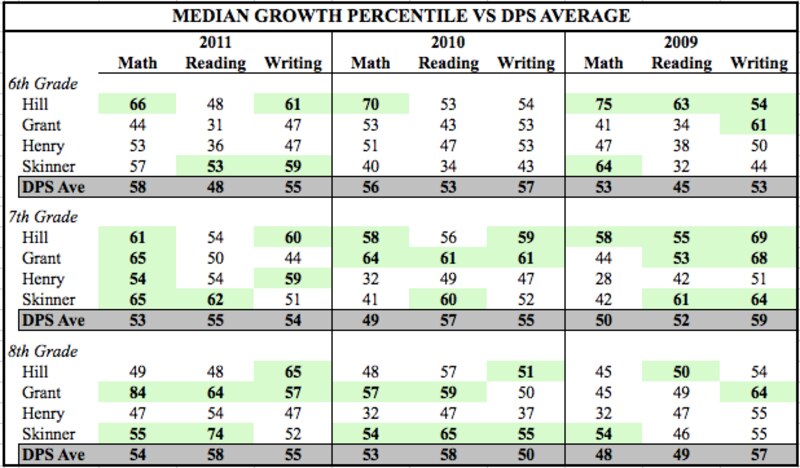

Shocking suggestion — but there is a simple way to check academic growth through CDE’s Colorado Growth Model, available at Schoolview. And at the end of this piece is a chart with the median growth percentile score, for each grade, for the past three years, at the four middle schools the authors cite. This chart comprises all 108 data points from the past three years, which are then each compared to their respective district average. 108 flowers in a field – but instead of choosing which selective few to carefully pluck from obscurity and arrange into a centerpiece under the spotlight, let’s go ahead and cultivate the entire bunch.

Cultivating the entire field

How did these schools compare when one looks at their whole crop of 108 growth scores (which include the four chosen so carefully)?

-> Over the past three years, these four schools performed better than the district average for growth just 42% of the time (45 scores out of the 108);

-> These four schools failed to surpass the DPS average for growth in any single year (47% of the time in 2011, 36% in 2010, and 42% in 2009);

-> These four schools failed to surpass the DPS average for growth in eight of the nine measured subject areas over three years.

These are growth scores: the proficiency scores are even worse. Across Denver’s traditional middle schools in 2011, only one in every three children left 8th grade with basic proficiency in at least a single subject.

Now, don’t misunderstand, there are some good things happening at several of these schools: Skinner is coming off a terrific year where they had growth percentiles above 50 in all subjects – an achievement for which they have not received nearly the credit they deserve. Hill is remarkably solid and, by itself, outperformed the District. There are groups of students with whom these schools are doing fairly well, and some remarkably well.

But these are exceptions, not rules. The authors also chose one of the only two possible (out of 27) data points where Henry outperformed the district in growth. Selective florists, these board members.

Data, upside down

There is a small but consistent rising tide of academic improvement in Denver, and traditional middle schools are getting better. But the schools these authors selected are lagging this tide, not leading it. And true to form, the choice of these specific four schools was selective as well — for there is a separate unmentioned group of four other traditional middle schools. When all eight are ranked by their 2011 average growth score, the authors selected schools finishing 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 7th (out of 8) . The schools they ignored ranked 3rd, 5th, 6th, and 8th (out of 8).* Very selective florists.

Selectivity such as this is okay when arranging bouquets – but it is specifically not okay when making decisions on educational options for children. These two members of the board of education are telling parents that if they choose any of Denver’s traditional middle schools, their kids will get a quality education. But that is just not true – there is tremendous variation in traditional middle schools (as in all schools), and more often than not, these schools are doing less well than their peers. But no matter:

“Tell us to start making well-supported neighborhood schools the key to real school reform.”

If traditional neighborhood schools are key to our future, surely the students graduating from them are equipped to face the demands of a college preparatory high school, and eventually the modern workforce?

Again, no. Let’s examine 8th grade average proficiency for 2011 at the four schools the authors selected. At Hill, it is 52% – there is only a one in two chance that a student leaves the school with basic skills in just one of reading, writing, or math. And that is the high water mark. At Grant, it’s 44%. At Skinner, 36%. At Henry, 35%.

And guess what? Those are the four traditional middle schools doing the best.

At the other four traditional middle schools, average proficiency in 8th grade is 33%, 25%, 25%, and 23%. In 2011, 8th grade average proficiency across all eight traditional middle schools is just 34% — or about one in every three students. Does that sort of academic record really make traditional schools “the key to real school reform“?

The bar for responsible behavior from the governors of our school system needs to be higher, for this is not okay. It is not okay for board members to tell parents that their traditional neighborhood middle schools are the “key to reform” when their students have less academic growth than the DPS average and only one of every three graduating 8th graders has basic skills. It is not okay to selectively choose four statistics and claim some providence of truth.

And it is expressly not okay to tell parents that these schools are the best we can do for their kids. Read the claim again:

“But the data are clear that neighborhood middle schools are exceeding the growth expectations of the Denver Plan. These schools are actually performing better than the district average, including all the newer schools.” [my emphasis]

The first part of this claim deserved analysis to see if it was true or not (it wasn’t). The second part, that traditional neighborhood schools are “performing better than […] all the newer schools” is so preposterously wrong that no amount of selective manure can make it flower.

In 2011, two new middle schools that began in the past three years ranked first and ninth respectively for academic growth — not just in DPS, not solely among middle schools, but out of the sum total of the roughly 1,780 K-12 public schools in Colorado. Somehow in their call for truth, the two best middle schools for academic growth in Denver slipped past their listening ears (as did others). There is no hearing aid that can cure that sort of intentional deafness. And there is also no reason parents in traditional middle schools should not be told of these options and the differences in academic growth so they can decide for themselves which schools their kids should attend.

Why make such demonstrably false claims?

What should puzzle everyone reading this is: Why? Why make such absurd claims for traditional neighborhood schools — claims that can be debunked in less time than it took the Rockies to lose another game? Why segregate one group — traditional neighborhood middle schools — and make patently false claims of superiority?

Well, it’s election season, and the Op-Ed provided both mimicry and political cover for any candidates with whom these existing Board members share ideology. Election season means everyone digs in and guards their ideological turf. Election season is ultimately about the votes of adults, not the academic success of kids.

And that’s the unfortunate point – this sort of perverse logic is what one gets when ideology eclipses truth: selective bouquets of carefully arranged data points, talking points, and pointless rhetoric. Four data points picked from a field of 108 and presented as definitive evidence. Board members who wrongly accuse the administration of lying; who leak information to the press to damage their colleagues; who resort to legal shenanigans; who fail to understand, disclose, or manage finances. All of this may be part and parcel of the viciousness of local educational politics, but at the point where board members are telling parents that schools are doing better than average when data shows the exact opposite, and are simultaneously silent about new options that are among the best in the state, well, it’s time to stop.

For this slavish devotion to ideology – the insistence that school type is what matters — goes against an argument that has been made over and over again on these and other pages, and which is critical to making any lasting improvements to public education: no one type of school guarantees success. Most parents understand this intuitively — there are some excellent traditional schools, charter schools, and innovation schools. There are some pretty lousy traditional schools, charter schools, and innovation schools. Parents are different, and kids are different, and no single type of school has a priority claim over all others.

Denver’s board members should focus first on school quality, regardless of type, and they should not be selectively distorting data to make any group of schools look better than they really are. For the truth the data tells us is that, particularly in middle school, we need the best of all types of schools so that we may no longer have the worst of any.

—-

*Note: The eight traditional middle schools that compose this data are Grant, Henry, Hill, Kepner, Merrill, Noel, Skinner and Smiley.

About our First Person series:

First Person is where Chalkbeat features personal essays by educators, students, parents, and others trying to improve public education. Read our submission guidelines here.