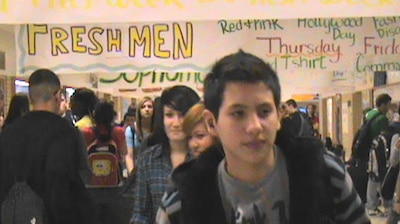

When North High School started offering night classes in September, students did not rush in.

Instead, they trickled in slowly until, as grades went home and graduation checklists were consulted, they filled one computer lab and then another.

At 4:30 p.m. Thursday, a time when most classrooms have gone dark for the day, dozens of students sat in front of computers in hopes of making up lost credits and graduating on time.

“They’re realizing, hey, May is not so far away,” said Matt Larson, a North language arts teacher who runs the night school, more formally known as a student engagement center.

Denver Public Schools opened four such centers across the city this school year, part of its multi-year, multi-pronged campaign to keep more students in school through graduation.

Earlier Thursday, DPS Superintendent Tom Boasberg and Denver Mayor John Hickenlooper celebrated signs that work is paying off at a news conference (see video) at another Denver high school, CEC Middle College.

“This is not happening in any other city in the United States,” Hickenlooper said of numbers showing more students enrolled in Denver high schools, taking tougher classes and on track to graduate.

“All those doubters,” the mayor said, “all those people who were giving up on our kids, giving up on our schools – step back.”

Strategy one: Intervene early with ninth-graders

Like many urban districts, DPS focused its initial reform efforts on elementary schools.

That began to shift in 2006 after Denver oilman Tim Marquez announced he was pledging $50 million to help ensure a lack of money would not stop any DPS graduate from going to college.

High schools were in the spotlight as district leaders scrambled to address a 50 percent graduation rate and to prepare students to take advantage of the college promise.

Jeannie Peppel, who is in her sixth year as principal of John F. Kennedy High School, said her job has “definitely” changed.

“We’re much more intentional about the work that we’re doing,” Peppel said. “We’re much more collaborative. We are using data that we haven’t before.”

All DPS principals were given the explicit goal this year of keeping 85 percent of their freshmen on track to graduation – meaning those ninth-graders must have earned 60 credits by year’s end.

The freshman year is critical for many students. One analysis found half of DPS ninth-graders who fall behind in credits will later drop out of school.

Six weeks after classes began in August, Peppel and her staff pulled numbers on every ninth-grader’s attendance and course progress. They found 58 percent were failing more than one class.

All of those 115 students received some type of intervention, from being assigned a peer counselor to a referral to the school social worker to being “adopted” by an administrator or a counselor.

“I have 12 adoptees,” Peppel said. “We call them our KOC’s, which is ‘kids of concern.’ ”

At mid-year, the number of students failing more than one class dropped to 59. That means 77 percent of Kennedy students are now on track to graduate, which is better but still below the 85 percent goal.

Districtwide, five of 13 DPS high schools were meeting the goal after the first semester. DPS’ overall rate of ninth-graders on track to graduation is 83 percent, compared to 68 percent in 2007.

“The focus this year with the high school target of 85 percent means we look at our ninth-graders earlier than we might have and put some plans in place,” Peppel said.

Curious, she analyzed how many of her struggling freshmen attended a ninth-grade academy, launched by DPS three years ago to help prepare students for high school.

Only two of the 115 students had gone to the summer sessions.

“That was eye-opening,” Peppel said. “That tells me the value of the ninth-grade academy.”

Strategy two: Get more students into ‘credit-recovery’

At North, as many as 60 students show up nightly for computer-based classes between 4 p.m. and 7 p.m.

Another 240 students use the computer curriculum, called Apex, during the day – lunch, free periods – to make up for classes they’ve failed earlier in their high school careers.

Steven Sanchez, a senior, is making up a geometry class he failed as a sophomore when he admits attending school was not his first priority.

He particularly disliked geometry, he said, because he didn’t understand it and he didn’t want to look stupid in class.

“I’m regretting it a lot,” Sanchez said of his ditching, now that he’s got a full class load and no margin of error during his last semester of high school. “I should have just went.”

Before a system like Apex, which spread to all DPS high schools this year, Sanchez’ main option for making up the math class would have been summer school.

And getting into summer school is not so easy. Because seats are limited due to increasingly scarce dollars, high schools often only allow older students in desperate need of credits to attend.

“A lot of times, you had sophomores not being able to get in to make up their credits,” said Nancy Werkmeister, North assistant principal, “so then they fall further behind and they get disenfranchised.”

Enrollment in DPS’ credit-recovery courses has nearly quadrupled in the past year, from 600 students in fall 2008 to more than 2,400 in fall 2009.

At the same time, the number of students earning credits in those classes had dropped. DPS switched to Apex, known for its online Advanced Placement courses, after fielding complaints from students.

“We’ve really been hearing students say, we went through credit recovery last year but we didn’t learn anything,” Stefanie Gurule, DPS’ director of student re-engagement, said Thursday. “We want to make sure they learn something and they’re prepared.”

North students had a 32 percent completion rate of Apex classes in the first semester, the highest of any Denver high school.

Larson, who oversees the evening classes, credits a model where four North teachers are assigned to the two labs.

In one lab, a math teacher and a science teacher work with students taking those classes. In the other lab, an English teacher and a social studies teacher work with students on those subjects.

“Kids today have so many different learning styles,” Larson said. “This is just another avenue.”

Most of the North students in credit-recovery classes are juniors and seniors, though 60 are freshmen making up classes they failed in their first semester. Another eight are former dropouts.

Sanchez, the senior re-taking geometry, will graduate on time this May if he passes every single class he’s now taking. He expects to do so, and he said he even likes geometry, a little, this time around.

“I get to work at my own pace,” he said, then shrugged. “It’s better than summer school.”

Nancy Mitchell can be reached at nmitchell@pebc.org or 303-478-4573.