In the corner of art teacher Barth Quenzer’s classroom is a door decorated with pictures of famous works of arts — and famous monsters.

Behind the door lives the “Artivore,” an imaginary monster who feeds on art and plays a central role in Quenzer’s classroom. Kindergarteners feed it scraps of paper, a group of fifth graders is writing a book about it, and countless students have tried to imagine what it looks like.

But Artivore’s origin story reveals the most about Quenzer’s teaching style. The art monster was the brainchild of a kindergartener, Jack, who simply began wondering what was in the closet.

Since then, Jack and his successors have built up the mythology of the Artivore, gradually adding details from what it dreams about to what it eats. Quenzer has turned the monster into a teaching tool to help explain different aspects of the artistic process, from the generation of interesting ideas to the letting go of bad ones.

Here’s an interactive tour of Quenzer’s classroom. Hover over the black and white dots to take a closer look at the tools Quenzer uses to run his classroom (and click here to view a larger version):

The evolution of Artivore is representative of the open-source approach Quenzer, an art teacher at Brown Elementary School in northwest Denver, takes to his teaching. Quenzer, who has been at the forefront of Denver’s implementation of the state’s arts instruction standards, uses everything from student input to the state mandates to shape the way he runs his classroom. And he has extended that inclusive approach to the kind of learning he inspires in his students.

(Quenzer is also one of the panelists at Chalkbeat’s event how to use art in classrooms on Thursday, July 17th. See here for more.)

Quenzer’s classroom often rings noisily with students’ voices as they work in groups and bounce ideas off each other. But the clamor of his classroom and his students’ independence mask the groundwork he lays.

Each class is constructed around concrete ideas on how students learn best, ideas that come out of his own observations from eight years of teaching at Brown.

When Quenzer began teaching, he started noticing trends in the way students of different ages learned.

“He was listening to students from the perspective of what was essential to their learning and identifying what was enduring,” said Capucine Chapman, the district’s fine arts coordinator and a mentor to Quenzer.

For example, Quenzer noticed that kindergarteners focus primarily on their own projects and don’t collaborate well.

“They run around, telling their own story,” he said. “By second grade, they are such good collaborators that all they want to do is work in the context of their own peers.”

So Quenzer made collaboration a central part of his instruction for second grade and provided opportunities for kindergarteners to improve their ability to work together.

Those kinds of instructional adaptations, he said, have been supported by the state’s grade-level standards for arts instruction, which went into effect in 2009. Denver Public Schools is in the process of testing out and refining assessments tied to the standards for each grade level, a process to which Quenzer is contributing.

Quenzer is also working with a group of other teachers and Chapman on a district-supported project called the “Trajectory of Learning.”

“If an idea’s a good idea, how can we extend it?” said Chapman. The project aims to combine what teachers like Quenzer have learned from their own classrooms with the state mandates in order to provide teachers guidance on implementing the grade-level standards.

Quenzer hopes the ideas will help other teachers begin to be more responsive to their own students and create a space for student-driven ideas.

“[What] if we can design something like curriculum that serves [students’] individual developmental needs?” said Quenzer.

For example, Quenzer never introduces a project assignment with a direct instruction but rather asks students if it’s something they’d like to do. If they say no, he asks them why and attempts to adjust the project to their desires. When a project comes to a close, he checks back in with the class to ask what went well and what didn’t.

“It’s a feedback loop,” Quenzer said. “The kids have become involved in the prototyping process [for my teaching].”

Just as Quenzer is using student feedback to refine his teaching, he’s trying to create opportunities for students to participate in each other’s work in order to grow as artists. The philosophy extends to everything from the basic layout of his classroom, which has “table teams” where students work together, to cleanup at the end of class, when older students leave beads and other small art supplies where they fell for the youngest students to pick up and use in their own art.

And students get the chance to edit their own work as well. Most projects in Quenzer’s class go through multi-week cycles of refinements, with students editing and adjusting their initial work.

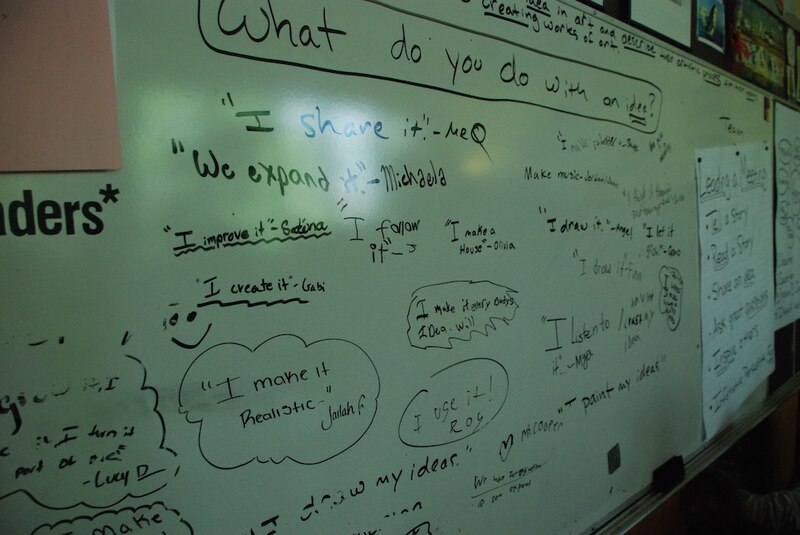

On a spring afternoon towards the close of school, he kicked off class with a group of third graders with a discussion of “what to do with an idea.” In previous classes, students had drawn what they thought an idea looked like, as a living thing, and built homes to protect their ideas.

“You have to be kind to your ideas,” Quenzer told his students.

The students spent the first 15 minutes of class practicing how to share their ideas and critiquing each other’s projects.

And as students dispersed to their tables, they launched into creations of their own design. All Quenzer provided was the initial discussion and the art supplies.

This kind of undirected learning that Quenzer’s students say takes place in few other classrooms.

“In most classes, you have lots of instructions,” one girl said. “I like being able to do what I want.”

But that doesn’t mean it’s easy for students. “Some projects are very hard,” she said.

For example, when Quenzer gave third graders the challenge of creating “stitch-monsters” from cloth without using glue, he gave them no other instructions on how to put the monsters together. They had to independently plan out all of the steps to produce the monster they’d created in their minds. Students struggled through the process, from teaching themselves how to sew to figuring out how to sew on body parts and deciding when to add the stuffing.

“There’s no one way to do it,” Quenzer told a struggling student. “There’s only the way you do it.”

And that’s where the rigor comes into Quenzer’s free-form classroom, he said. Rather than follow specific instructions, students must problem-solve to address the dilemmas Quenzer lays out for them.

His students say that process helps them learn in their other classes.

“Art is hard to understand,” one student explained. “It makes it easier to understand things in other classes.”