Links to full report and appendices

Members of the State Board of Education got their first in-depth look Wednesday at the recommended shape of new evaluation systems for teachers and principals, and they also got a sense of how much work remains to be done.

The were briefed on the massive report of the State Council for Educator Effectiveness by co-chairs Nina Lopez and Matt Smith. Lopez stressed the theme of a work in progress, saying, “We don’t expect to get it right off the bat.”

After the presentation and occasional board member questions, Chair Bob Schaffer, R-4th District, jarred the packed hearing room a bit when he said, “I’m not giddy about the process and the report.”

A moment earlier, Elaine Gantz Berman, D-1st District, had said, “I think this work is absolutely remarkable. I rarely get giddy over huge reports like this.”

Schaffer, a vocal advocate of parent choice in education, made it clear he wasn’t criticizing the dedication of the council nor the quality of its work. “I’m not enthusiastic about where the law has put this particular process.”

Rather than complex systems like that suggested in the report, Schaffer said, “The most efficient guarantor of quality” in education “is a marketplace.”

He said parent choice “probably is the most direct measurement of success and performance.”

Senate Bill 10-191, which assigned the council to develop recommendations for new evaluation systems, requires at least 50 percent of educator evaluations be based on student growth as measured by tests. Schaffer said, “It seems to me there might be an incentive … to push your bad students out of the school. … Am I wrong about this?”

Noting the kind of consistency and uniformity he sees in SB 10-191 and the council’s recommendations, Schaffer said, “I never thought that was the way” to reform education.

The council isn’t proposing a single, detailed statewide system for judging educators; that wasn’t its assignment. But its report is intended to provide the foundation for the rules and regulations that the board will issue next autumn to implement Senate Bill 10-191, the landmark law that requires that at least 50 percent of annual teacher and principal evaluations be based on student growth.

Key tasks that CDE now assumes include creation of a detailed model evaluation system, development of ways to measure student growth where CSAP scores aren’t available, and building resources and materials that districts can use in their own systems.

So administrators, teacher and parents won’t have a full sense for how the new system might work until the board issues its regulations, and perhaps not until after a trial run is done in a selection of districts, starting later this year.

Under the terms of SB 10-191, the evaluation requirements won’t go into “finalized” full use statewide until the 2014-15 school year.

An economic study done for the council estimates a cost of $42.4 million to get evaluation systems up and running statewide, with other continuing district costs for evaluations and support of educators who need improvement.

The final report is about 170 pages, plus the appendix, and contains some 60 recommendations.

Key recommendations

A key recommendation is that a fourth level of effectiveness be added to the three listed in the law, which are highly effective, effective and ineffective. The additional level would be called partially effective and be inserted between effective and ineffective. SBE member Marcia Neal, R-3rd District, praised this recommendation.

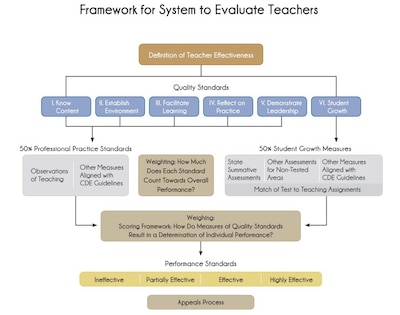

The core of the council’s recommendation are two definitions of effectiveness, one for teachers and principals, and two corresponding sets of standards on which effectiveness will be judged.

Here’s the definition of teacher effectiveness:

Effective teachers in the state of Colorado have the knowledge, skills and commitments that ensure equitable learning opportunities and growth for all students. They strive to close achievement gaps and to prepare diverse student populations for postsecondary success. Effective teachers facilitate mastery of content and skill development, and identify and employ appropriate strategies for students who are not achieving mastery. They also develop in students the skills, interests and abilities necessary to be lifelong learners, as well as for democratic and civic participation. Effective teachers communicate high expectations to students and their families and find ways to engage them in a mutually supportive teaching and learning environment. Because effective teachers understand that the work of ensuring meaningful learning opportunities for all students cannot happen in isolation, they engage in continuous reflection, on-going learning and leadership within the profession.

Here’s the definition for principals:

Effective principals in the state of Colorado are responsible for the collective success of their schools, including the learning, growth and achievement of both students and staff. As the school’s primary instructional leaders, effective principals enable critical discourse and data-drive reflection about curriculum, assessment, instructions and student progress, and create structures to facilitate improvement. Effective principals are adept at creating systems that maximize the utilization of resources and human capital, foster collaboration and facilitate constructive change. By creating a common vision and articulating shared values, effective principals lead and manage their schools in a manner that supports the school’s ability to promote equity and to continually improve its positive impact on students and families.

The council’s draft recommendations list six standards for teachers, including content knowledge, creation of respectful environments for all students, facilitation of learning, leadership, taking responsibility for student growth and professional development.

There are seven standards for principals, including leadership in strategic thinking, instruction, school culture, human resources, management, external relations and student growth.

See the full text of standards for teachers here and those for principals here.

The council also made recommendations for measurement and scoring frameworks that will be used in evaluations. Again, those are areas where additional work will be done.

The council’s recommendations are a mix of common features that should apply statewide and other components that districts will have flexibility in using. For example, the six teacher standards are common, but districts may have some flexibility in how they weight those standards when doing evaluations.

“We spent a lot of time considering what are the ‘shalls’ and what are the ‘mays,’ ” Smith said.

The council recommends that district evaluation systems must meet overall state requirements and that districts be required to either review and update their own evaluation systems as necessary or use the model system to be fleshed out by CDE.

Much remains to be done

SB 10-191 requires that at least 50 percent of teacher and principal evaluations be based on student growth. CSAP scores, which are the foundation of the state’s Colorado Growth Model, will be part of that, but not all grades and all academic subjects are tested by CSAP.

The council is recommending that CDE develop state assessments for science and social studies, work with school districts to development measurement and assessment methods for non-CSAP subjects and to organize a state study of how to best measure academic outcomes for students in preschool through grade 2.

An amendment to SB 10-191 also assigned the council to recommend an appeals process for teachers who lose tenure – non-probationary status – because of a low evaluation. That piece of the council’s work isn’t due until next January so isn’t included in the report. The appeals recommendation will go directly to the legislature, not through SBE.

Another piece of future business for the council is developing recommendations for evaluation of licensed educators who aren’t in a classroom full-time – content specialists, instructional coaches, counselors, media specialists and others.

“Only about 30 percent of teachers in our state are teaching subjects where CSAP data is available,” Lopez noted.

The board is expected to discuss the report and perhaps hold a public hearing at its May meeting before receiving draft regulations from Department of Education staff in June. After further hearings in August, September and October, the board is expected to adopt final educator evaluation regulations in November.

Cost of new evaluations

The cost study was done for the council by the Denver consulting firm of Augenblick, Palaich and Associates. According to the council’s April 7 newsletter, the consultant “estimates that districts could incur a one-time start-up cost of $53 per student. For ongoing annual evaluation, estimates for teachers and principals vary depending on their rating of effectiveness. For example, increased supervision and training for a teacher with an ‘ineffective’ rating could run as much as $3,873 a year. Teachers and principals rated as ‘effective’ could cost between $406-$531 extra due to increased data analysis and more frequent evaluations than in the past.

“The council recognizes that these costs will be a burden when districts already are under severe financial pressure. To alleviate the impact on districts, the council will advise the state to provide the maximum possible timely, high-quality assistance to districts. Districts, in turn, may need to explore reallocating resources and securing additional funding.”

The cost study doesn’t include potential CDE costs for implementing the program.

The department recently has reorganized it work for a greater focus on educator effectiveness and hired two new staff members to work on the issue. After the department and the state board finish their work next autumn, the terms of SB 10-191 give lawmakers review over the proposed effectiveness regulations during the 2012 legislative session.

Background on the council and the law

The council has a somewhat complicated history. It originally was created by executive order of then-Gov. Bill Ritter in early 2010 and later that year given an expanded role after being incorporated into SB 10-191.

The 15 members represent a careful balance of education interests, from teachers to a charter school representative as well as school board members, administrators, a businessman, a parent and an academic. see member list.

The council’s work moved in fits and starts last spring and summer but accelerated late in the summer after staff was hired and the group increased the frequency of its meetings. The panel met for the equivalent of 30 full working days, Lopez said.

The Rose Community Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Colorado Legacy Foundation, the Daniels Fund, the Donnell-Kay Foundation, JPMorgan Chase and Co. and Common Good have provided support for the council and other CDE work on educator effectiveness.

SB 10-191, championed by Sen. Mike Johnston, D-Denver, was the focus of a bitter fight at the end of the 2010 legislative session. The Colorado Education Association opposed the bill, while the American Federation of Teachers-Colorado and education reform groups worked for its passage.

Several key compromises aided passage of the bill, including legislative review of the SBE’s regulations, the long implementation timetable and the requirement that the council submit a proposed appeals process directly to lawmakers.

In addition to educator evaluations, other key parts of the bill include provisions by which non-probationary teachers can be returned to probation if evaluations warrant that, requirements for mutual consent in teacher placement and consideration of evaluations when teachers are laid off. Some of those parts of the law already have gone into effect.

The educator effectiveness law is part of a broader package of education reforms passed by the legislature from 2008 to 2010, including the Colorado Achievement Plan for Kids (significant portions of which remain to be implemented), a new accountability and improvement system for districts and schools, and creation of unique identifiers for teachers.

Major funding questions loom over some of those measures, including the cost of the new state tests required by CAP4K and the price tag for implementing new evaluations. The legislature cut $260 million from basic school funding for this year and is on track to cut $250 million more for 2011-12, although some lawmakers still are working to reduce that figure.